By Marianne Lombardo and Nicole Brisbane

Let’s be clear about something. The New York State Education Department’s (NYSED) actions are probably more about adults saving face than helping kids.

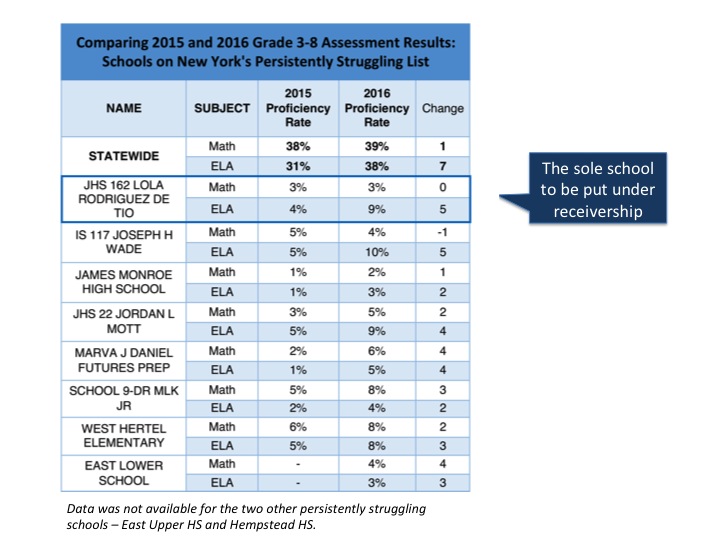

When NYSED announced on Wednesday that just one of the ten schools on the state’s persistently struggling list (see our earlier report School Interventions in New York State: Abandoning Students in the Worst-Performing Schools) would move to “receivership” because the other nine had attained “demonstrable improvement,” they neglected to mention that:

- The median proficiency rates at the schools they upgraded were 5% in math and 6% in reading.

- Proficiency rates in reading statewide jumped 7 percentage points, a large part of which was likely due to changes in the assessment. None of the schools NYSED praised for “progress” saw their reading proficiency rates improve anywhere near the statewide average (see table below).

- If a school starts at a 6% proficiency rate and improves about 3 percentage points each year, today’s 3rd graders will be out of high school by the time the school reaches the statewide average of 38-39%.

Instead, Education Commissioner MaryEllen Elia issued this statement:

And, what is this “demonstrable improvement”? It’s based on a set of indicators, chosen by each school. Half are low-expectation outcome goals. For example, one of East Lower School’s targets was that 22% of their students would score “partially proficient” and above. This means that 78% of students could score at the lowest level of performance in math and yet the school would meet the target. The other half contains highly subjective — and thus largely unverifiable — process measures (e.g. “curriculum development and support” and “teacher practices and decisions”). If these things don’t directly link to academic success, shouldn’t they be barred from trumping it?

Consequences for the sole school to be put under receivership – JHS 162 aka Lola Rodriguez de Tio – are still being worked out. The city may close or merge the school, or submit an improvement plan within sixty days to avoid the state stepping in. JHS 162 is already one of the City’s 86 Renewal Schools, and is already a “community school,” so it will be interesting to see what a new improvement plan will look like. But, unlike the other nine schools, they will be able to access state funds set aside to help and will have a broader array of policy levers available through which to improve.

We know making sweeping changes in proficiency rates is hard and requires long, sustained, creative effort. It’s not something that happens overnight. But, it’s not okay to settle for incremental progress. Taking no action and rewarding minimal change is hurting students rather than helping them. NYSED is making it seem like these dismal results should be enough to satisfy parents and stakeholders. Well, they aren’t.

Students deserve to be reading and doing math on grade level and until they are, we need to make sure schools have the support and full range of options available to them to enable that change. Receivership continues to be labeled as punitive instead of creating a system where we’re actually acknowledging that these results are not acceptable and that we need concrete, clear plans with accountability in place to see the change our students deserve.

Here’s another way to think about it. A recent piece by poet/activist Clint Smith in the New Yorker refers to a 2005 court case brought against the state of North Carolina for its failing school system, in making the case for how those inequities served as a catalyst for the recent civil unrest in Charlotte. The judge, in issuing a report on the state of schools in Charlotte, concluded: “The most appropriate way for the Court to describe what is going on academically at CMS’s [Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools] bottom ‘8’ high schools is academic genocide for the at-risk, low income children.”

Convince us otherwise that New York’s continual abandonment of students in schools where just 5-10% of kids are proficient is not such another example.