There are at least two phenomena on which most progressive education reformers and teacher union leaders agree: our school system is inadequately and inequitably funded and our system of teacher education and training does not adequately prepare new and continuing teachers for the emerging demands of an increasingly modern and diverse classroom. In fact, the latter failure magnifies the former insofar as the neediest students in the most under resourced, inequitably funded schools are taught by a stream of underprepared rookie teachers year after year.

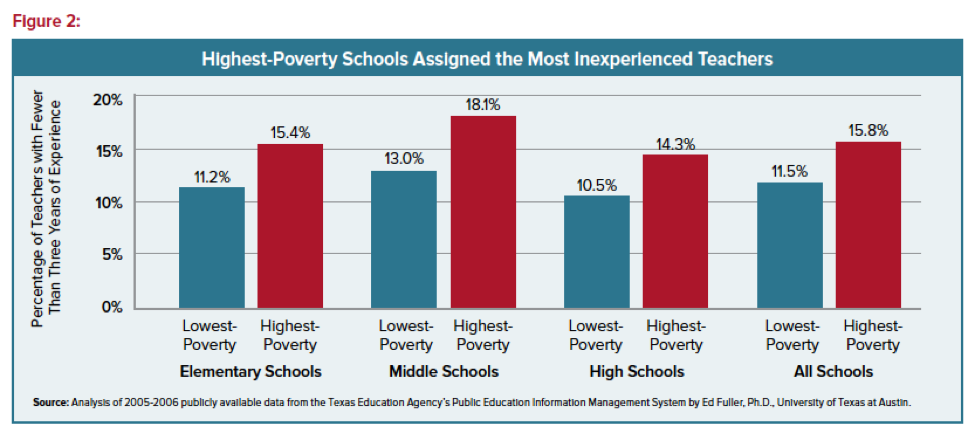

Figure 2: Highest Poverty Schools Assigned the Most Inexperienced Teachers

High need students in under resourced schools do not just experience one or two bad teachers over the course of a 12-year academic career. They experience a string of them, grade after grade, as more experienced teachers who have improved after a year, two, or three in the classroom transfer to more affluent schools and school districts. It is not uncommon for a low-income student to be taught by a rookie teacher in grades 1, 2, and 3. And because teacher quality is the number one in-school influence on student achievement, affected students in under resourced schools end up falling further and further behind their more advantaged peers. Societal inequality worsens.

Because political leaders have not wanted the U.S. Department of Education to determine which higher education programs, including teacher preparation programs, are of sufficient quality to warrant taxpayer support, the task of teacher preparation program quality control has been outsourced in large part to accrediting agencies. These agencies are peer organizations of institutions of higher education or postsecondary training programs recognized by the U.S. Secretary of Education to consecrate institutions of higher education and individual postsecondary education programs as being sufficiently adequate in terms of quality to participate in federal student financial aid programs, and hopefully foster institutional and program improvement as per the accreditation process.

If you think our accreditation system whereby existing suppliers effectively decide who can be suppliers is a case of the fox guarding the taxpayer’s henhouse, you would be correct. Indeed in many ways, the heart of the quality problem in teacher preparation and higher education in general is that the system’s chief guardians of quality, accreditors, are financially dependent upon dues-paying members—higher education providers—who in general are averse to student outcomes-based measures of program quality.

Recent history validates that the current teacher preparation program accreditor, the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP), is no better than other accreditors consecrated under this flawed system. In the case of teacher preparation though, the flaws of the accreditation system are magnified insofar as teacher candidates that postsecondary education programs fail to train adequately go on to have enormous influence on the outcomes of K-12 elementary and secondary education children and thus in too many cases perpetuate a cycle of education poverty.

In our view, for teacher preparation accreditation to be effective, dependence on schools of education as guardians of teacher preparation quality must end. Because the current teacher education accreditor has shown it cannot and will not reform itself, a new type of accreditor, not dependent on schools of education and their personnel but instead on the employers of graduates from schools of education and teacher preparation programs, should be created. Chief state school officers, urban superintendents of schools, and charter school network leaders should band together to form an accreditor focused on: (i) the learning gains of elementary and secondary school students taught by the graduates of teacher preparation programs seeking accreditation, and (ii) the assessments of employers of whether the graduates of teacher preparation programs are adequately prepared for classroom service.

In the attached, we describe a tactical path that makes use of entrepreneurial opportunities as much as governmental action.

Maybe our suggested path isn’t the best. As former New York State Education Commission David Steiner puts it, “the key issue is not only to break the monopoly of CAEP, but to create a powerful force to press existing education schools into a performance-based accountability frame. There is a huge difference between creating a boutique accrediting agency for a few non-traditional teacher preparation programs, and creating a through line to a whole-scale transition of accrediting practice.”

He’s right, but the process of accreditation reform needs to be kick-started anew. We can’t afford to wait.