The 2023 Social Mobility Elevator rankings are the first college ranking system to center race and ethnicity, to include state context, and to levy a penalty for using legacy preferences.

It might seem like an odd time to refresh the Social Mobility Elevator (SME) rankings that Education Reform Now (ERN) first released in 2020. The U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges rankings are at a low point after many of the top-ranked law schools and medical schools announced they would no longer respond to the magazine’s surveys. While only two four-year colleges have made the same public pledge, the response rate for the reputation survey has plummeted to just 34%. And no wonder, since the reputation survey is an absurd exercise in which college presidents and chief admissions officers are asked to identify the best study abroad programs and the best First-Year Experience at colleges where they do not work. The Secretary of Education, Miguel Cardona, has called college rankings a “joke” and told an audience in March, “It’s time to stop worshiping at the false altar of U.S. News & World Report. It’s time to focus on what truly matters—delivering value and upward mobility.”

Driving social mobility is one of the most important reasons for higher education.

Given the cost of college and the deep income inequality in America, however, metrics such as graduation rates, earnings, debt repayment, and other quantifiable measures matter tremendously in determining the value of college. Additionally, we think the power of rankings to call attention to colleges that are having a positive impact on social mobility makes them a useful, if crude, tool.

We first created the Social Mobility Elevator rankings and are refreshing them now to focus on some of the things we think matter in evaluating four-year colleges, namely, their power to serve as engines for social mobility.

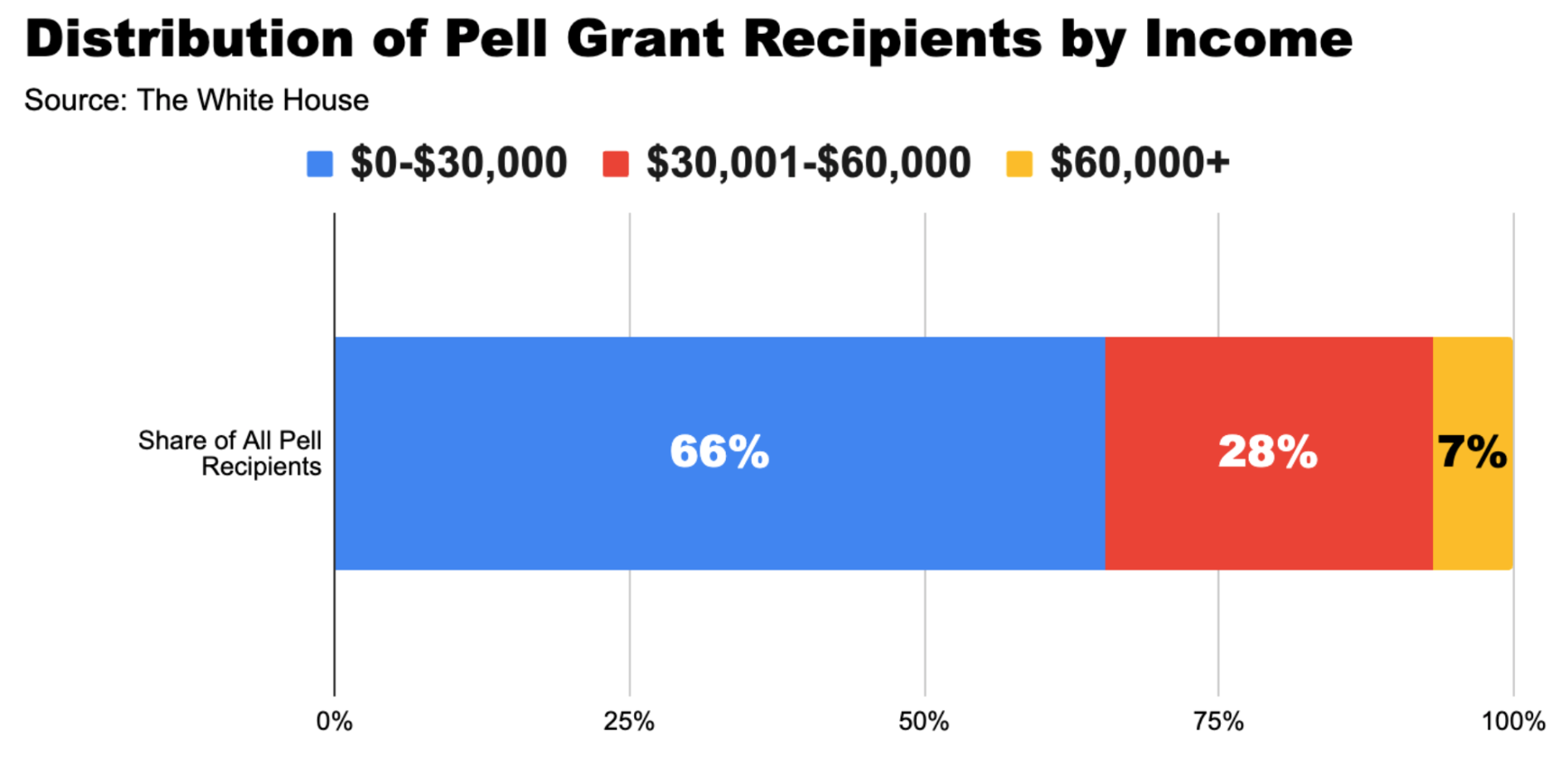

The first Social Mobility Elevator rankings were designed to measure the impact four-year colleges have on upward social mobility for low-income students, who we identified as students who received Pell Grants for the U.S. Department of Education. Nearly all Pell Grant recipients come from a family that makes less than $60,000 per year, while two-thirds come from households with incomes below $30,000. About a third of all undergraduates in the U.S. received a Pell Grant in 2020.

For each college, we looked at the number of Pell-eligible students enrolled, what percentage of all undergraduates were Pell eligible, and what percentage of students with Pell Grants graduated with a bachelor’s degree.

The first version of our rankings made it clear that while higher education can function as an engine for social mobility, it does not always do so.

There are too many four-year colleges where too many students leave with debt but no bachelor’s degree or where graduates earn so little that they struggle to make progress on student loans years after completion of their degree. There are also too many colleges that admit too few students with Pell Grants to have much impact.

Many of the colleges in that latter category, with very low percentages of Pell-eligible students, do very well in the U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges rankings. They also happen to do quite well in other rankings systems that put more emphasis on a college’s ability to help students move into a higher income quintile. If U.S. News and Washington Monthly both put Stanford University, MIT, and Princeton in their top five, why do we even need the Washington Monthly rankings, which ostensibly count social mobility as a major component? It is true that students from the poorest income quintile who get into Stanford or MIT do indeed typically go on to be much richer than their parents. The problem is that so few of those low-income students actually go to a Stanford or an MIT or to any of the colleges that are so hard to get into that some have come to call them “highly rejective” instead of “highly selective.” As a result, highly rejective colleges have very little impact on social mobility. They are more like poverty escape hatches through which a relatively tiny number of individuals can pass.

We do not need poverty escape hatches. We need social mobility elevators, big ones, designed to lift many people up.

If you are looking for students with Pell Grants, you will find many more of them at less-rejective public universities than at the colleges that top most rankings. One important exception to college rankings highly rating wealthy colleges with low rates of enrollment for Pell-eligible students is the Economic Mobility Index released by Third Way in 2022, which does an excellent job in shining a light on those colleges where students from low-income households enroll and graduate. That is the intention of the Social Mobility Elevator rankings, but we have also used this refresh as a chance to rethink what we mean by social mobility and what our rankings are meant to achieve.

What’s new in the Social Mobility Elevator rankings?

In brief, a lot. (For a full discussion of the methodology, click here.)

Our aim is to call attention to the colleges and universities that have a significant impact on social mobility, which we define in terms of both increasing economic mobility and shrinking the racial and ethnic gaps in bachelor’s degree attainment, which have remained static or even worsened in the past two decades. We want to highlight the colleges that have the largest impact on social mobility in order to drive more support for them. These colleges already do a good job of enrolling and graduating an economically, racially, and ethnically diverse student body, but they could do an even better job if they received more state funding or implemented and expanded evidence-based programs and practices that increase retention, graduation, and career earnings.

Here are the main changes to the 2023 Social Mobility Elevator rankings.

3. The earnings premium index measures the percentage of students

earning more than the median income of a high school graduate with no

postsecondary credentials six years after starting college.