The culture wars. The Science of Reading. Fights over school closures. The explosion of private-school choice in red states. The simmering controversy over the potential creation of “religious charter schools.”

Given all that has happened in the last few years, advocates for public education reform may feel left behind. Or maybe caught in the crossfire. The old debates about charter schools, standardized testing, and funding levels suddenly seem like Old Hat. And multiple prognosticators are declaring “the death of education reform.”

I think that’s wrong. Calls for reform are not going to cease until our archaic system is refashioned so that it serves children, especially kids from low-income backgrounds, who rely on public education to give them a fair shot at the American Dream.

But the big problem is this: Many Americans have a reflective tendency to defend traditional public schools. They believe traditional public schools serve all students and give everyone a fair chance to succeed. Public schools, as the cliche goes, “are the great equalizer.” While this anachronistic belief pervades all parts of our society, this is particularly true within the Democratic party and the Democrats I talk to.

Those of us who work in education policy know how naive this belief is. The education system as currently structured does more to reinforce social inequalities than to overcome them. The achievement gaps based on race and class have remained stubbornly in place over the past decade, despite K12 education spending rising more rapidly than almost any other sector of our economy.

How do we persuade them that the current system is deeply flawed and that it is highly skewed toward serving special interests, not low-income kids? Here’s my answer: Talk about equal access to public schools. Denounce educational redlining. Advocate for public school choice and Open Enrollment. Use the language of civil rights.

Almost 70 years ago, the Supreme Court ruled that the segregation of schools on the basis of race had to end. They said that it was unconstitutional for little Linda Brown to be turned away from her neighborhood public school and sent to one farther away, just because she was African American. In the unanimous opinion, Chief Justice Earl Warren promised that, from now on, the public schools would have to be “available to all on equal terms.”

My research—as well as that of many others—has shown that our current public schools are still not available to all American children on equal terms. Our school assignment system is built on government-drawn maps that determine who can—and who can’t—enroll in coveted public elementary schools. Like the redlining maps of the early 1900s, these policies ensure that, in the first quarter of the 21st century, the most valuable government services are still reserved for wealthy and politically powerful families. Working-class families, people of color, immigrants – most of them are boxed out.

In today’s world, little Linda Brown wouldn’t be turned away from a public school because of her race, but because of her address. I fear that’s no great improvement.

In my old neighborhood in Los Angeles, living on one side of the street or another can determine whether your child goes to a school with 75% reading proficiency or 16% reading proficiency. Because of the zone maps, wealthy families bid up the price of real estate, and often it will cost $300,000 more to buy a home that is in the zone, rather than a comparable one just outside. This is often the true cost of a “free” public education in our country.

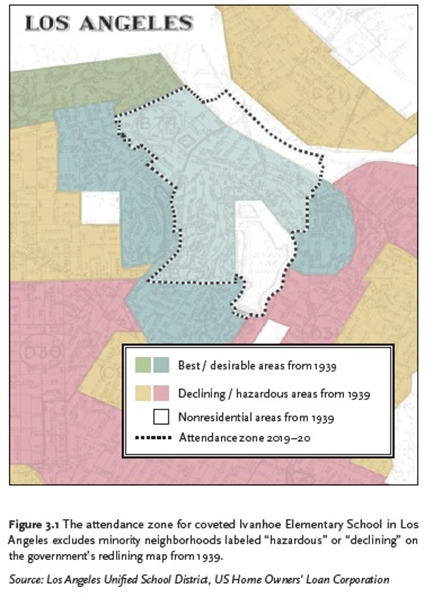

I’ve found that it is particularly powerful, when talking to Status Quo Defenders who are not steeped in these issues, to point out how much our K12 education system has in common with the redlining era of the 1930’s and 40’s. Everyone knows how wrong it was for the government to discriminate against low-income people in this way.

What’s more, the maps don’t lie. For my book, I worked with a designer to show how the modern-day attendance zones for many coveted public schools mirror the racist redlining maps that were drawn over 80 years ago. And they still discriminate against those parts of town with significant populations of immigrants and people of color. Look, for example, at the attendance zone for Mount Washington Elementary, a coveted public school in our old neighborhood of Northeast Los Angeles.

Of the seven public elementary schools in the neighborhood, only one school has more than 9% white students, and that’s Mount Washington at 59%. Throughout the neighborhood, residents vote overwhelmingly Democratic. And, within the zone of Mount Washington Elementary, many of the homes will prominently display Black Lives Matter signs. But there is little, if any, outrage that the low-income Hispanic families who live within a mile, but outside the misshapen zone, are not welcome.

For those of us who believe in the public schools, ending this educational redlining has to be Priority #1. We need to move on from this archaic and discriminatory practice of turning children away from school because of where they live. Low-income kids need a fair shot at getting into these elite public elementary schools.

That’s where Open Enrollment comes in. Open Enrollment laws and policies allow children access to public schools outside of the one they are assigned to based on their address. In theory, Open Enrollment can end this fatalistic link between the neighborhood you grow up in and the quality of the public school that you’re assigned to. Arizona, Colorado, Wisconsin, and Washington, DC for example, have seen huge growth in the numbers of children taking advantage of Open Enrollment policies.

Unfortunately, these laws and policies often have loopholes that prevent them from being effective levers of change for the families who need it most. In many states, it is “optional” for districts to offer Open Enrollment seats. In some states, districts are allowed to charge “tuition” for OE students. And almost all states have a “space available” exception that allows the most coveted schools to keep their doors shut to those who live even blocks away (since the school is already full with families who crammed into the zone).In Arizona and Wisconsin, there are loopholes that allow a district to categorically deny an OE application if the child has a disability, no matter how minimal the services the child needs.

Open Enrollment policies are often seen as another program to provide some degree of limited school choice. But what we need are Open Enrollment policies that are designed—and sold—as the solution to the civil rights issue of unequal access to schools. And these policies need to confront and defuse the common objection of the Defenders of the Status Quo: Open enrollment will hurt “the neighborhood school.”

Here are a couple options to consider:

First, a state could adopt a law creating student-based zones, rather than school-based zones. A student would be guaranteed an equal opportunity at enrollment at any public elementary school within a certain radius of their home, perhaps five miles. If a school didn’t have the capacity to serve all the students who wanted to attend who were within that radius, they’d have to hold a random lottery, just as public charter schools do.

Second, a state could require any public elementary school that has selective admissions (meaning it turns away some prospective students because it is “full”) to hold back or reserve at least 10-15% of its seats for children who live outside of the zone.

This isn’t so different from what the Houston school district did a few years ago when it required magnet schools – if they were to keep the “magnet” label and the extra funding that came with it – to reserve 15% of the seats for students outside the attendance zone. Terry Grier, the former Superintendent of Houston Independent School District, told me that this was Houston’s way of opening up what had been quasi-private public schools that only served the wealthy and powerful.

These are eminently reasonable reforms that would start us down the path of ending strict geography-based school assignment. They allow schools to keep their neighborhood character, but they also shine light on the civil rights issue of access to public schools. Of course, reformers should also be looking for ways to close the common loopholes associated with Open Enrollment laws.

The added benefit is that true Open Enrollment can serve as a reminder of the advantages of public education, rather than private. While private providers are free to turn kids away, public schools are—in principle—required to take all comers and provide an equal opportunity for all kids to attend. But we can’t make the argument very strongly right now, because it’s not really true. Open Enrollment is a way to restore the longstanding promise of the public schools that are truly available to all.

Education reform is certainly not dead. But we reformers do need to capture the public’s attention, take back the moral high ground, and show the public, vividly, that the current system is a descendant of our nation’s exclusionary, discriminatory past. Focusing on school access as a civil right is a great way to do that, and Open Enrollment laws are a vehicle for giving kids from low income backgrounds better options that the current system denies them.

It’s time.

If you want to learn more, please access the materials below:

1) Redling and School Current School Districts

2) Magnet School Reform In Houston

You can download a PDF version of this post here.