Over the last decade, school districts across the country have embraced centralized choice programs where families have the option to pick a public school outside of the one they were assigned to. We recently highlighted Colorado and Washington DC as exemplars, but cities like New Orleans, New York, Newark, etc. all have policies in place where families can choose a diverse array of schools, regardless of their home address.

But do these policies have a positive impact on student achievement?

Although early studies have indicated that giving families more options for public schools does so, it’s challenging to pinpoint “school choice” as the main reason for improved student performance. Many of the districts that introduced centralized choice also made other changes simultaneously, making it difficult to confidently attribute the changes solely to school choice. That is why the Zones of Choice program in Los Angeles makes for a unique case study, as examined in a recent paper by University of Chicago Professor Christopher Campos.

In 2012, the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), responding to mounting community demands for improved educational access, established the Zones of Choice (ZOC) Program. Rather than being restricted to an assigned high school based on where a student lives, families in this program were granted the option to select any high school within a broader zone. This broader zone was formed by combining several neighborhood assignment zones, allowing families that were previously assigned to only one high school option to instead have multiple options.

The ZOC encompassed approximately 30-40% of LAUSD high school students in 16 different zones. Students within the ZOC were more likely to be from low-income families, more likely to be Hispanic, and on average have lower standardized test scores than their district peers. Notably, during the ZOC’s implementation, the remaining LAUSD maintained the conventional model of assigning schools based on home address.

Creating a choice program in a specific part of the district while the rest of the district operated under the status quo model allowed for an organic, within-district experiment.

Campos uses this natural experiment to compare changes in student performance within the zone to changes in student performance outside of the zone between 2008-2019. He also compares how students performed within the ZOC before and after implementation of the program.

His research concludes that student achievement in the ZOC grew at a faster rate than students outside of the zone. Student achievement on standardized tests, high school graduation, and college enrollment increased markedly for students who lived in the ZOC areas.

Key findings from the study include:

- Students increased their Math and English scores in 11th grade compared to comparable students living outside of ZOC, moving .16 standard deviation by the seventh year of the program, effectively eliminating the achievement gap between ZOC and non-ZOC schools that existed.

- SAT scores within the ZOC made substantial increases (although participation rates did not) compared to non-ZOC schools.

- Within ZOC high schools, graduation rates increased by 10-12% and college enrollment increased by 25% from the baseline mean.

- Schools that had the most pressure to improve were the ones experiencing the largest improvements in quality

The results here are noteworthy. There are several possible explanations for these findings

- As parents were no longer assigned to a neighborhood school, high schools had to compete for student enrollment. Therefore, Campos finds schools that were lower-performing before the ZOC was implemented grew the fastest over the course of the study.

- Suspension rates increased and absenteeism decreased, which implies there may have been a focus on student discipline in ZOC schools.

- Parents prioritized school achievement when making a choice in which high school their child should attend, which has not been shown as a consistent decision-making factor in other research. Campos believes this could be for two different reasons.

- ZOC is fairly homogeneous (88% Hispanic and 79% in poverty), and parents, consequently, didn’t necessarily use student demographics as a proxy for school achievement.

- Unlike district-wide controlled choice programs, ZOC parents had a condensed set of choices in a smaller market. Campos states this meant that parents faced “manageable choice sets which may help them avoid the choice overload issues present in other school choice settings” and allowed them to focus on a smaller set of schools and focus more on the academic results of each school. As parents focused on academic achievement, lower-performing high schools had to change instructional practice and improve student outcomes.

The research presented here strongly suggests that when parents can choose schools outside of the one they were assigned to, all students benefit. Schools, in order to attract students, make significant changes to school culture and pedagogical practices. Parents, in turn, become more selective in how they choose schools.

The study does raise outstanding questions that further research should examine. For example: do parents do better under a more condensed choice with a few schools rather than district-wide choice programs we have seen across the country? If so, what is the right amount of choice? Lastly, this study focuses on school choice at the high school level. Would there be a difference in academic achievement if this were expanded to earlier grades, as is being implemented currently in LAUSD?

Professor Campos’s research stands as one of the first studies isolating the impact of within-district school choice on student achievement. The findings are significant, providing solid evidence that expanding public school options positively impacts academic performance, especially for students farthest behind.

For further information:

Read the full study here.

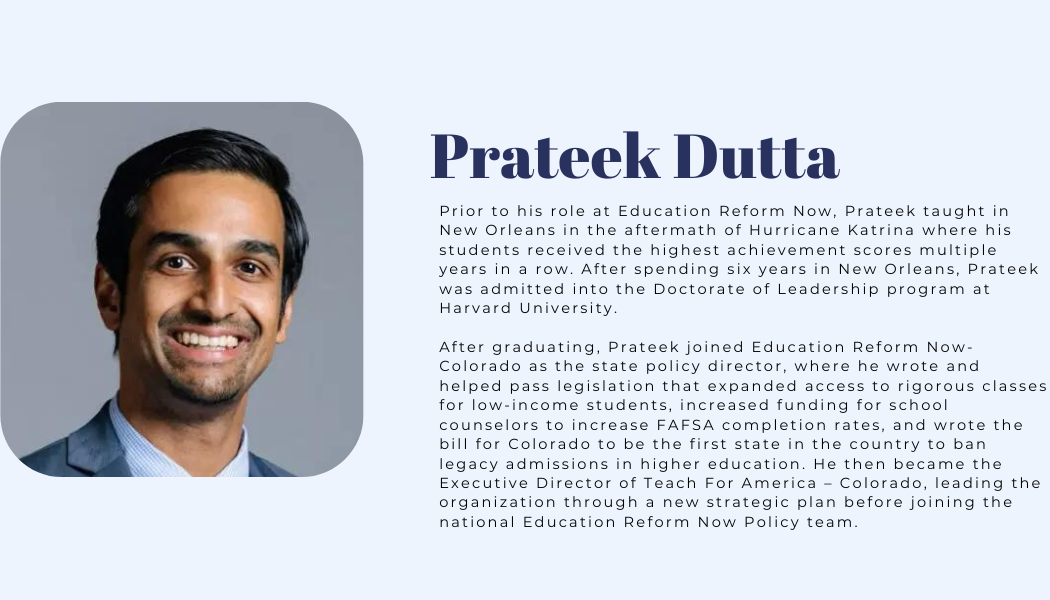

Learn more about the author here.