Should college come with a money-back guarantee? A recent Brookings op-ed argues, “Yes,” and highlights several innovative colleges offering prospective students guarantees of on-time graduation, employment, and post-graduation earnings. But while we relish the thought that some colleges seem to be prioritizing student outcomes over their own bottom-lines, some of these self-initiated programs may be too good to be true.

To be clear, a money-back guarantee for college performance in improving student outcomes is a promising development, especially in a time of economic uncertainty about the returns of a college education. Perhaps all the chatter at the federal level on “college quality,” “shared responsibility,” and “risk-sharing” has prompted colleges to be proactive in how they measure and produce value for their students.

But there are two apparent flaws with the design and implementation of the money-back guarantee programs that individual colleges have thus far put forth: (1) scope and (2) cost, and how these two factors intersect to impact college student performance.

Presumably, a college would only offer prospective students a money-back guarantee if: (a) it expects that it can easily meet it; that is, if it thinks very few students will end up needing the money-back guarantee, (b) it thinks very few students who do need it will actually qualify for it, or (c) it can pass on the expense. All three are problematic for students.

Consider Davenport University, a private college in Michigan where students in select programs are promised up to three extra semesters tuition-free if they do not earn employment within their field within six months of graduation. Davenport imposes strict eligibility requirements on its guarantee. To receive the promised benefit, students must:

- Work directly with Career Services within 2 semesters of attending;

- Complete at least 150 hours of work relative to the chosen field prior to graduation;

- Achieve a final GPA of 3.0 or 3.5 for select programs;

- Be willing to travel or relocate to a new market anywhere in the country;

- Have a documented job search beginning no later than 2 semesters prior to graduation: and

- Have sent no less than 50 customized resumes and cover letters spanning geographic markets and industry sectors.

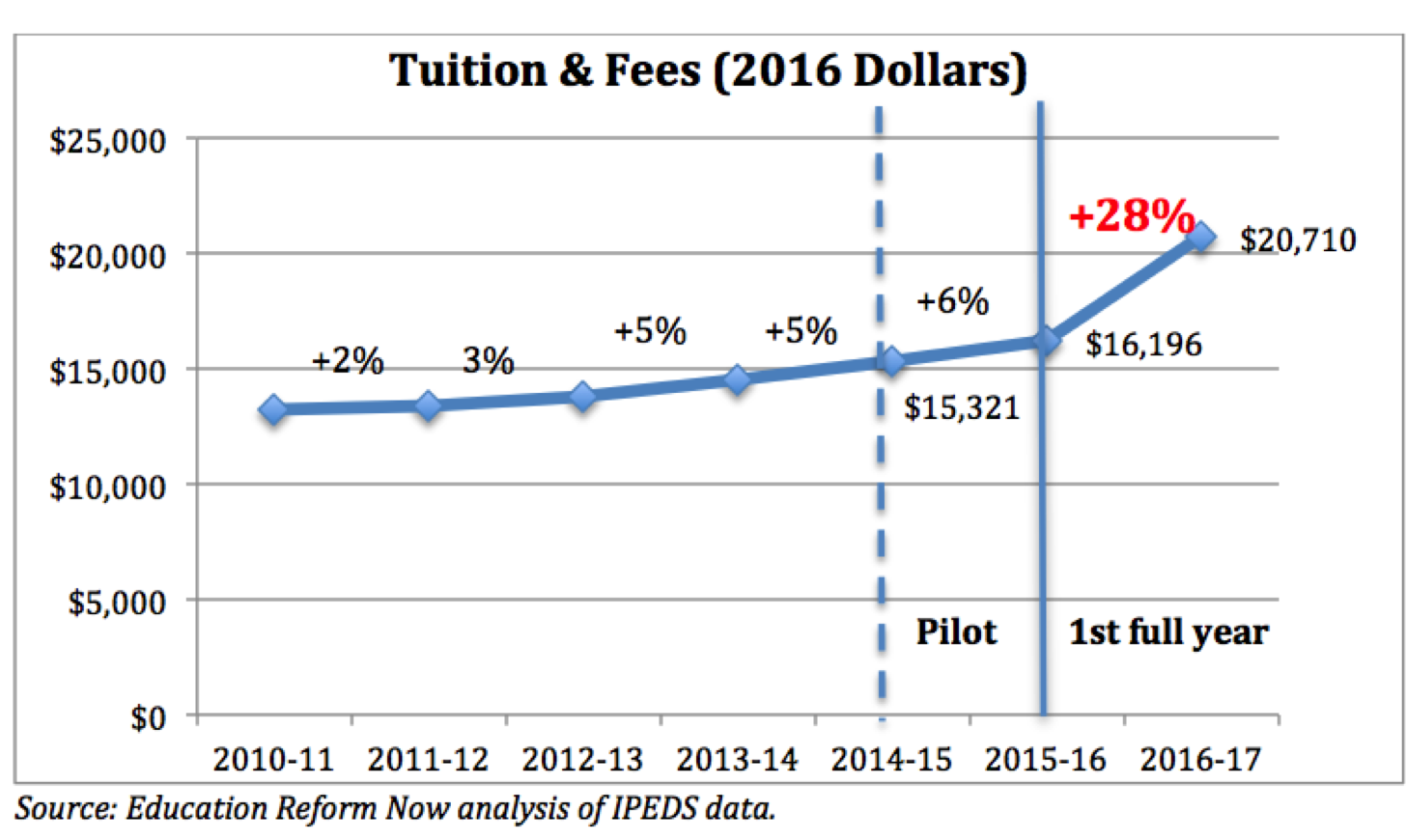

If somehow a lot of students are able to meet those stringent requirements, then not to worry — Davenport is covered. At Davenport, tuition and fees jumped by 30 percent the year after the program was fully implemented for all students. See chart below.

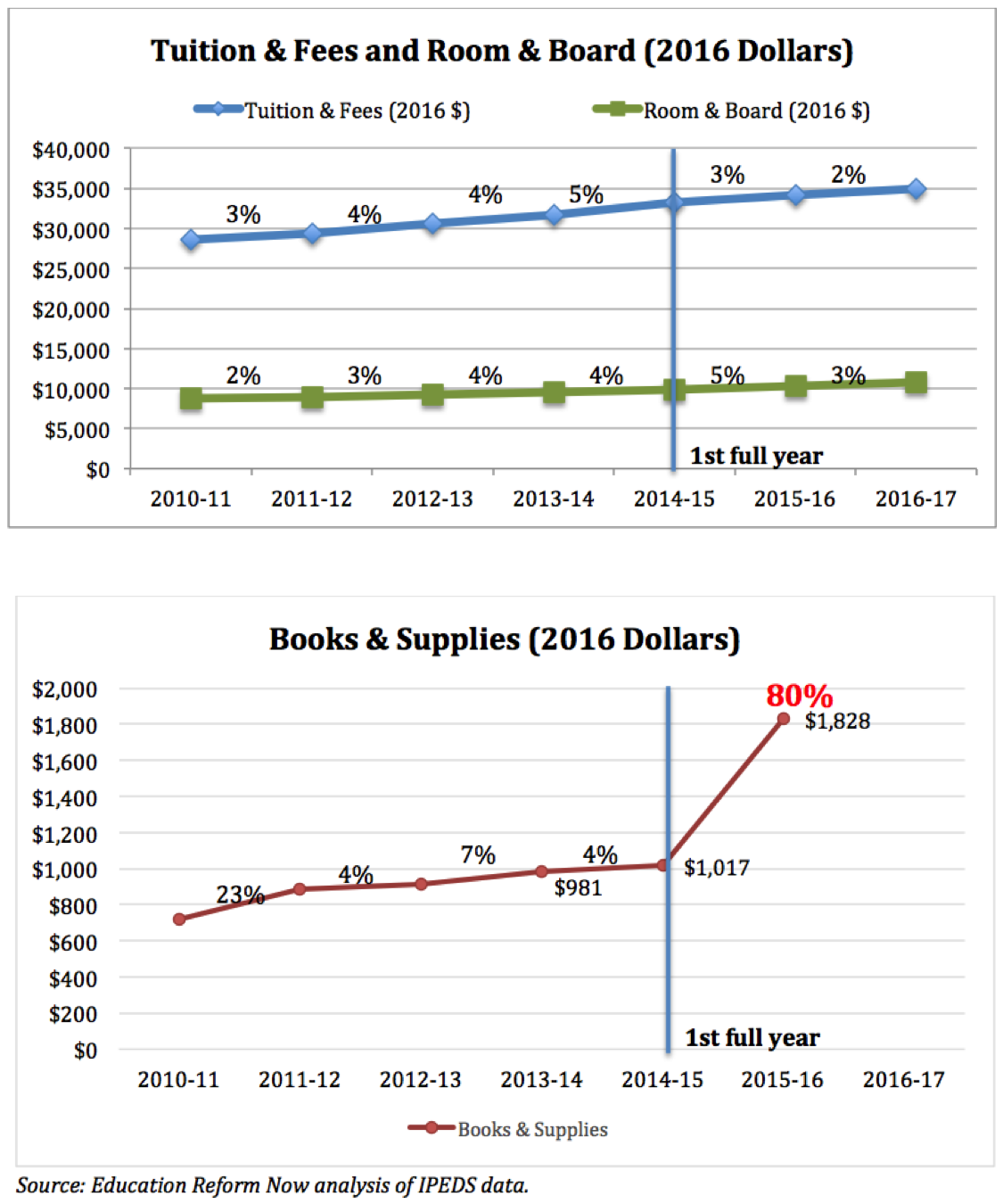

The same up-charging pattern occurs at Adrian College, another private college in Michigan, although it’s more hidden.

Adrian promises to offer “loan repayment assistance to students at no additional cost…and fully funds the cost for students to participate in this program” (emphasis added). Interesting. While published tuition and fees and room and board grew between 2 and 5 percent every year since the program started, the cost for books and supplies has jumped by 80 percent!

Then there are the places where up-charging is unlikely to cover institution costs associated with a money-back guarantee. They’re just not likely to come through.

Consider Alma College in Michigan, the University of Evansville in Indiana, and the University at Buffalo in New York. All promise to pay for some tuition beyond the 4th year if a student meets their academic responsibilities, but fails to graduate within four years. But currently less than half of students graduate within four years at Alma, and just over half graduate within that time frame at Evansville and Buffalo.

What these issues around scope and cost ultimately come down to is to what degree will institution-initiated, money-back guarantees lead to actual improved student performance on a wide-scale basis?

We fear the answer might be very little, because aside from making a minimal investment in borderline “bubble” students who might need extra time to graduate, find suitable employment, or those who graduate but need help with loan repayment, the underlying program structures embraced to date seem either to have extremely tight eligibility requirements, pass off institution costs for failure, or just seem pretty unrealistic.

So while money-back guarantees might seem promising, it’s hard to see just yet if pioneering colleges truly have the interests of students at heart. The goal for policymakers, if not institutions, should be to ensure that money-back guarantees inspire true education improvement for students as opposed to working as just another easy-money gimmick run by colleges.