ASPIRE ACT SUMMARY

SPONSORED BY SENATORS COONS (D-DE) & ROSEN (D-NV)

National Need

- There are about 80 four-year colleges that have first-time, full-time student dropout rates in excess of 80% –measured six years from initial enrollment. These schools serve approximately 400,000 students.

- At the same time, schools that do graduate most of their students within four years of initial enrollment – some of our nation’s wealthiest schools – enroll very low percentages of low-income students — far below the number of qualified students available. UVA. has a 10% Pell enrollment rate; UNC with the same admissions standards has a 24% Pell enrollment rate. The UVA.’s of the world need to be pushed.

- There are approximately 90,000 Pell Grant recipients with SAT scores of at least 1120 (the median score for students at selective colleges) that are shut out of top-flight universities, because of reasons ranging from inadequate financial aid to admissions policies that undermine diversity like the legacy preference, according to a recent Georgetown study.

ASPIRE Proposal sponsored by Senator Chris Coons (D-DE)

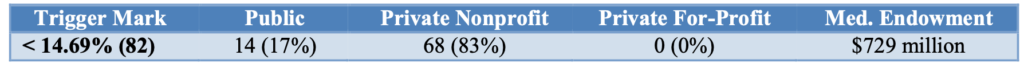

- Wealthy colleges that enroll very few low-income students (< 14.7%) have to improve access rates over four years or pay a fee to participate in the federal student loan program. Penalty fees will support new assistance funds to under resourced, struggling colleges and a new competitive grant program for those institutions that do a good job of enrolling and graduating working class and low-income students.

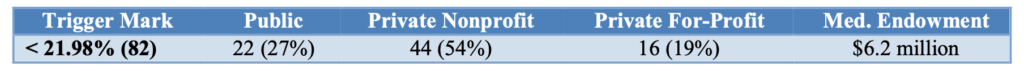

- If they choose to participate, under-resourced nonprofit and public colleges with low graduation rates (< 22.0%) receive up to $8 million to improve over five years. Participating colleges must meet accountability standards (i.e. raise graduation rates to above 22%) at the conclusion of that five-year period or return assistance funds over time.

- Included is a new competitive grant program for nearly all institutions to boost completion efforts. HBCUs and MSIs receive priority in award determinations. Appropriations are authorized at “such sums as necessary.”

- Colleges in the top 50% of Pell enrollment and top 25% of six-year graduation rates can apply for non- financial rewards, such as reduced regulations or bonus points in competitions.

Key ASPIRE Stats (2013-14 IPEDS Data)

- Bottom 5% Success Colleges

- Bottom 5% Access Colleges

List of Supporters

- College Summit

- Delaware State University

- Education Reform Now Advocacy

- Georgia State University

- Institute Higher Ed Policy

- Lincoln University (Pa.)

- NAFEO

- National Education Association (NEA)

- Princeton University

- The Education Trust

- Third Way

- Thurgood Marshall College Fund

- University of California

- Wilmington University

ASPIRE Act FAQ’s/Additional Talking Points

Q: What does the ASPIRE Act do?

A: Basically, ASPIRE does two things: (1) it pushes highly selective institutions with very large endowments to do their fair share to enroll qualified low-income students (they have to pay a fee to participate in the federal student loan program if they don’t enroll a bare minimum percentage of Pell Grant recipients), and (2) it supplies under-resourced colleges struggling to graduate students, many who are low- income, with what in essence are 100% forgivable, no-interest loans to help increase graduation rates.

More specifically, the ASPIRE Act provides that:

- Wealthy colleges that enroll very few low-income students (< 14.7%) have to improve access rates over four years or pay an approximate $7,000 per missing low-income student fee to participate in the federal student loan program. Penalty fees are then channeled to under resourced, struggling colleges that serve high percentages of low-income students and to a new competitive grant program for those institutions that do a good job of enrolling and graduating working class and low-income students.

- If they choose to participate, under-resourced colleges with low graduation rates (< 22.0%) receive up to $8 million to improve over 5 years. But participating colleges must meet accountability standards at the conclusion of that five-year period or return ASPIRE Act provided assistance funds over time.

- Included is a new competitive grant program for nearly all institutions to boost completion efforts. HBCUs and MSIs receive priority in award determinations. Appropriations are authorized at “such sums as necessary.”

- Colleges in the top 50% of Pell enrollment and top 25% of six-year graduation rates can apply for non- financial rewards, such as reduced regulations or bonus points in competitions.

Q: What does this bill do to address student debt?

A: The students most likely to default on their loans are those who do not graduate: College dropouts are

over three times more likely to default on their student loans than those who graduate.

By expanding access to institutions that graduate almost all of their students and increasing resources devoted to boosting graduation rates at institutions serving high numbers of low-income students (who often take on loans), the ASPIRE Act aims to improve outcomes so that more students actually graduate with a meaningful degree and in turn are able to pay off their student loans.

Q: Doesn’t the ASPIRE bill rank colleges?

A: The bill does include eligibility criteria for institutions to gain access to completion funds based on relative standing as per multiple measures, much like ESSA similarly targets additional resources to school districts performing in the bottom five percent as measured against peers. And the ASPIRE bill does penalize low Pell grant enrollment colleges based on a percentage enrolled cut score, much like the Higher Education Act currently penalizes colleges with cohort default rates in excess of 40 percent in any given year. But the bill does not rank colleges overall.

Q: How much will this bill cost?

A: This is a self-financing bill that requires no new money. If Congress wants to appropriate additional funds for provisions authorized, it’s free to do so. Sen. Coons (D-DE) sits on the Senate Appropriations Committee.

Q: Is there a research base to suggest that this carrot and stick approach will work?

A: Yes. We’ve seen both work in higher education. With respect to our experience with sticks in federal higher education policy, note that some 10 years ago Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IO) threatened to withdraw wealthy colleges’ tax-exempt status if they didn’t improve their college affordability. And despite the storm of protest, many of those colleges ultimately expanded their financial aid programs to offer “no-loan” promises not only to low- and working-class students but also middle-income students.

We’ve seen the same phenomenon with the Obama administration’s focus on for-profit colleges and the threat of lost financial aid eligibility. The percentage of for-profit revenue devoted to instructional expenses at for-profit colleges has increased over 25 percent — with revenues on marketing and profits declining — and graduation rates at four-year for-profit colleges have also increased by nearly 40 percent.

In terms of carrots, we’ve seen colleges readily embrace opportunities for flexibility, innovation, and improvement, like those supported under the Experimental Sites initiative, the First in the World program, and the College Access Challenge Grant. Outside of higher education, we’ve seen it work with the Race to the Top initiative. The U.S. Department of Education has identified a series of promising practices for states and institutions of higher education to undertake that boost completion.

Q: Is it problematic to set up a scheme where institutions have to pay back the federal government if they don’t meet certain conditions? Isn’t this a penalty?

A: Because completion funds with accountability provisions attached are provided on a completely optional basis for nonprofit and public institutions, it’s up to each college’s discretion whether to participate. The program is akin to a 100% forgivable loan with a very low bar for institutions to meet.

The bill would provide approximately $8 million to voluntarily participating low completion colleges over five years to boost their graduation rates above 22% (measured six years from the date of initial enrollment and only for first time, full time students). The funds do come with bare minimum accountability measures — if recipients don’t improve to that 22% graduation mark after five years, they need to start returning portions of the $8 million in aid. But those repayment terms are even more favorable than the current HBCU Capital Finance program that provides low-cost loans for repair, renovation, and construction needs. Current HBCU capital finance loans have to be repaid regardless of institution performance.

Q: How ASPIRE Differs from Other Higher Ed Accountability Bills

A: Current higher education accountability bills generally take one of two forms. Embrace of: (1) minimum eligibility standards applicable to all colleges in exchange for federal aid eligibility; (2) risk-sharing where bad colleges must put “skin in the game” and be responsible for a share of students’ bad financial outcomes.

The ASPIRE bill stands out for:

o Providing a financing structure that recognizes low-performing colleges need time and financial assistance to improve;

o Ensuringfornonprofitandpubliclow-completioncollegesthatparticipationis100%voluntary and triggers no exposure to general Title IV eligibility;

o Delimiting specific minimum benchmarks based on the bottom 5% institution performance level on two core purposes behind federal student aid: 1) access, and 2) completion;

o Targeting institutions for help that are underperforming as compared to similar institutions serving similar students; and

o Including for higher-performing institutions, particularly HBCUs and MSIs, competitive funds and non-financial rewards to continue improving.

##