February 1, 2023

Dr. Miguel A. Cardona

Secretary of Education

Mr. James Kvaal

Under Secretary

U.S. Department of Education

400 Maryland Avenue SW

Washington, DC 20202

Dear Secretary Cardona and Under Secretary Kvaal,

In order to address long-standing racial and ethnic gaps in bachelor’s degree attainment that could be exacerbated by a Supreme Court decision that may bar institutions of higher education (IHEs) from considering race in their admissions processes, the Department of Education (ED) should expand its collection of admissions data and disaggregate that data by race and ethnicity, as it already does for gender.

While racial and ethnic gaps in the attainment of a high school diploma have shrunk significantly since 1981, they persist in bachelor’s degree attainment. The high school diploma gap between Black and White adults has significantly narrowed, but Black adults remain 10 percentage points less likely to have a BA than White adults are.[1] Between White and Hispanic Americans, the bachelor’s degree gap has actually gotten worse: 38% of White adults have a BA, but just 21% of Hispanic adults do.[2] If these gaps are to shrink, policymakers, researchers, institutional leaders, equity advocates, families, and communities will need a better understanding of their causes.

Currently, ED does not collect data disaggregated by race and ethnicity for college applicants or admitted students, which creates a blind spot in understanding the sources of enrollment and degree gaps. Nor does ED collect data on legacy preferences or early decision and early action plans, three admissions practices shown to have detrimental effects on diversity and access at selective colleges. The addition of a question to the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) on whether a college considers legacy status in fall 2022 will be useful, but that data point will be much more powerful if it is paired with information on how many students benefit from legacy status.

While increasing transparency in college admissions of colleges and universities has always been important, it has become even more necessary in light of the ongoing attacks on policies aimed at advancing racial equity and diversity and the upcoming Supreme Court decision that may ban or narrow the consideration of race in admissions. Several studies of public universities in states that banned race-conscious admissions policies have found immediate and persistent declines in enrollment of Black, Hispanic, and Native American students.[3] After the elimination of race-conscious admissions in California and Texas, admission rates of Black and Hispanic students fell by 30 to 50 percent at the states’ most selective universities and underrepresented minority representation in their entering freshman classes declined.[4] In California, Proposition 209 deterred thousands of qualified students from applying to any UC campus and led others to enroll in institutions of higher education with lower completion rates and smaller financial returns.[5] These changes in enrollment led to long-term, negative effects on the income of Black and Hispanic residents in their twenties and thirties.[6]

These studies all relied on disaggregated institutional level data for applicants, admits, and enrollments; currently, it would be impossible to replicate such research on a national level, since those data are not available. If policymakers, researchers, advocates, IHEs, and students are going to understand the impact of existing admissions practices on access as well as the impact of the elimination of race-conscious admissions practices, should the Court decide that way, they will need richer information about the entire admissions process at public and private IHEs, including data on admissions practices that harm diversity and access.

Supreme Court decision aside, expanding IPEDS data will enhance ED’s ability to fulfill the Education Sciences Reform Act’s directive to “collect, report, analyze, and disseminate statistical data related to the condition and progress of postsecondary education, including access to and opportunity for postsecondary education.”[7] ED should use the authority granted to the National Center for Education Statistics to expand IPEDS to include three new Admissions components:

- Racial and ethnic demographic data for applications and admits, not just enrollments, in order to track disparities in access throughout the admissions pipeline and not just at its endpoint.[8]

- Whether an IHE considers an alumni relation in its admissions process and, if it does, the number of applications, admits, and enrollments that fall under this category, disaggregated by race, ethnicity, gender, and, when possible, socioeconomic status, in order to measure the impact that providing a legacy preference has on access and diversity.

- Whether an IHE offers an early decision and/or early action plan as part of its admissions process and, if it does, the number of applications, admits, and enrollments that fall under this category, disaggregated by race, ethnicity, gender, and, when possible, socioeconomic status, in order to measure the impact that offering early decision has on access and diversity.

The administrative burden imposed on IHEs by new IPEDS questions will be limited. Since most IHEs have open admissions policies and are therefore not required to report admissions data, almost three-quarters of them would be exempted from disaggregating data for applicants and admits; 87 percent would be exempt from reporting legacy data; and 97 percent would be exempt from reporting on early decision. Most of the institutions who would be required to report and disaggregate this new data are already collecting it through the Common App or their institution’s application and using it for internal purposes. The new requirements would merely make that data public and thus increase the transparency of and accountability for admissions practices that may harm diversity and access at some IHEs. Under-resourced institutions should be given time and support to ensure they have the ability to comply with existing and additional data-reporting requirements.

Increasing transparency is more than just a path toward greater accountability for institutions of higher education; it is a powerful signal the Biden administration can send to indicate its commitment to diversity and access in postsecondary education.

We value the Department of Education’s commitment to equity and opportunity in postsecondary education. We welcome the opportunity to work with ED to implement these changes to IPEDS and propose that the next step in this process would be to set up a meeting to discuss further. The lead contact on this letter is James Murphy, Deputy Director of Higher Education Policy at Education Reform Now. He can be contacted at james@edreformnow.org.

Sincerely,

ACCEPT

Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund

Association of College Counselors in Independent Schools

Bottom Line

College Promise

David Bergeron, College Unbound

DC Special Education Cooperative

Education Deans for Justice & Equity

Education Reform Now

Hildreth Institute

Kelly Slay, Assistant professor of Higher Education and Public Policy, Vanderbilt University

Julie J. Park, Associate Professor, Department of Counseling, Higher Education, and Special Education, University of Maryland, College Park

Michael Bastedo, Professor, Center for the Study of Higher and Postsecondary Education, University of Michigan

NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. (LDF)

NALEO Educational Fund

National Charter Collaborative

National College Attainment Network

National Partnership for Educational Access

National Urban League

New America, Higher Education Program

OiYan Poon, University of Maryland, College Park

Robert Shireman, Director of Higher Education Excellence and Senior Fellow, The Century Foundation

Sen. Andrew Gounardes (NY)

Soribel Genao, Assistant Professor, Department of Educational & Community Programs, CUNY

Sosanya Jones, Associate Professor, Educational Leadership & Policy Studies, Howard University

Steppingstone

The Education Trust

The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice

The Institute for College Access & Success (TICAS)

The Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP)

Third Way

uAspire

UnidosUS

W. Carson Byrd, Associate Research Scientist, Center for the Study of Higher &

Postsecondary Education, University of Michigan

Young Invincibles

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, Table A-2: 1947, and 1952 to 2002 March Current Population Survey, 2003 to 2021 Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey (noninstitutionalized population, excluding members of the Armed Forces living in barracks);1950 Census of Population and 1940 Census of Population (resident population).

[2] U.S. Census Bureau, Table A-2.

[3] Peter Hinrichs, “The Effects of Affirmative Action Bans on College Enrollment, Educational Attainment, and the Demographic Composition of Universities,” The Review of Economics and Statistics (2012). See also, Mark C. Long and Marta Tienda, “Winners and Losers: Changes in Texas University Admissions ost-Hopwood,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (2008), and Mark C. Long and Nicole A. Bateman, “Long-Run Changes in Underrepresentation After Affirmative Action Bans in Public Universities,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (2020).

[4] David Card and Alan B. Krueger, “Would the Elimination of Affirmative Action Affect Highly Qualified Minority Applicants? Evidence from California and Texas,” Industrial & Labor Relations Review (2005).

[5] Zachary Bleemer, “Affirmative Action, Mismatch, and Economic Mobility after California’s Proposition 209,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics (February 2022).

[6] Bleemer.

[7] Statutory Requirements for Reporting IPEDS Data, IPEDS Data Reporting System (2022-23).

[8] While we are not currently asking the Department of Education to expand the racial and ethnic categories currently collected, we note that in the future ED should disaggregate race and ethnicity data in IPEDs by the American Community Survey categories, which further disaggregate Asian American and Pacific Islander groups. While ED may need to give IHEs more time to collect data around such disaggregated categories, we urge ED to begin the process of working with IHEs now to ensure challenges faced by AAPI subgroups, and their root causes, can be better evaluated and addressed.

In wake of the on-going national college admissions scandal, every candidate for state or national office should be asked a simple question: “How do you plan to make college cheaper, fairer, and better?” Not just cheaper, but fairer and better because we’ve got serious equity and quality challenges in higher education.

A couple of weeks ago, we suggested four ways to make college cheaper. Today, we offer four more ways to make college fairer with a brief pro-con analysis of each.

Here we go.

Goal: Make College “Fairer” in Admissions, Enrollment, and Student Service. The admissions and financial aid systems are rigged to ensure selective colleges, including state flagships, are filled not with the most meritorious students but those from the highest income backgrounds. All too often, low-income and racial minority students effectively are shunted into under resourced, non-selective public four-year institutions and two-year community colleges — often due to inadequate high school preparation. Those qualified to attend selective, four-year colleges who under match into other institutions are 30 percentage points less likely to complete than equally qualified peers. And time and again, we see colleges with similarly qualified student bodies with similar characteristics generating wildly different rates of success with racial minority students. Bottom line: America’s education equity issues extend to higher education.

Goal: Make College “Fairer” in Admissions, Enrollment, and Student Service. The admissions and financial aid systems are rigged to ensure selective colleges, including state flagships, are filled not with the most meritorious students but those from the highest income backgrounds. All too often, low-income and racial minority students effectively are shunted into under resourced, non-selective public four-year institutions and two-year community colleges — often due to inadequate high school preparation. Those qualified to attend selective, four-year colleges who under match into other institutions are 30 percentage points less likely to complete than equally qualified peers. And time and again, we see colleges with similarly qualified student bodies with similar characteristics generating wildly different rates of success with racial minority students. Bottom line: America’s education equity issues extend to higher education.

Moderate Proposals:

Idea #1A & 1B: Use federal aid to advance college admissions reform. (A) Provide up to $50 million in aid to institutions that make use of “supplemental, class-based affirmative action” in admissions. (B) Ban the legacy preference, binding early decision, and donor preferences at any college that does not evidence “a meaningful commitment to diversity” (i.e. enroll and graduate a significant number of low-income and racial minority students).

Pros: Supplemental class-based affirmative action (i.e. in addition to race-based affirmative action) builds on past suggestion of former Harvard President Derek Bok and current College Board work. Preference ban recommendation echoes past proposal by the Hispanic Education Coalition and others.

Cons: Attacking the underpinnings of elite higher education admissions risks alienating members of the donor class. Regardless, touching any aspect of the admissions issues triggers an intense debate over race-based affirmative action. Privately, some may oppose pro-socioeconomic mobility and diversity admission reform policies fearing a backlash against race-based affirmative action. Publicly, opponents will argue reform efforts are intrusive and reflective of an elitist view of inequity in higher education opportunity.

Idea #2: Institute a higher education public service fee charged to colleges with indefensibly poor working class and low-income Pell Grant student enrollment levels. After being given time to improve, the public service fee can take the form of an increase in the recently passed GOP endowment tax on super wealthy schools or creation of a new, public service fee for participation in the federal student loan program charged to colleges that operate as “engines of inequality.” Higher education public service fee generated revenue should disbursed to HBCUs, minority serving institutions, and other under resourced, high Pell-serving four-year schools.

Pros: Pits elite colleges and their defenders against HBCUs and other high Pell-serving institutions. Works off of current law concepts (i.e. the GOP’s 2017 endowment tax and later inserted McConnell exception for Kentucky’s Berea College) as well as pending legislation (i.e. the Coons-Rosen ASPIRE bill) endorsed by the NEA, education reformers, and higher education leaders, including the University of California’s Chancellor and Princeton University’s President.

Cons: Will be characterized as a quota capable of being gamed and an attack on academic freedom. Prompts debate on affirmative action that consistently polls poorly.

Bold Proposals:

Idea #3: Link high school reform and improvement policies to any free college or debt-free college federal-state partnership proposal. Attach dedicated funds for, and condition, free college or debt-free college on implementation of high school reforms, including upgrading high school curricula for all, default placement of all students on a college prep academic track, supplemental tutoring and summer support for those academically behind, a college and career counselor in every high school, and district accountability for college enrollment, placement, and completion.

Pros: Fills a yawning gap in K-12 education debate without touching testing. Expands political coalition behind college affordability to K-12 advocates and interests. Good policy in that high school curricular rigor is the number one influence on college completion.

Cons: Expensive. Limited examples of successful high school reform and improvement. Pushing all students on a college prep track in high school triggers the “Is college really for everyone?” debate, which polls poorly.

Idea #4: Accountability for all colleges, all programs, and all student groups. As a condition of aid receipt by institutions of higher education, require college leaders to set ambitious goals on access, affordability, and completion for students overall and specifically those who are members of historically underserved and disadvantaged groups. Require that goals be set institution-wide and for targeted program areas of sufficient size within, such as STEM enrollment and student performance. Provide direct aid to institutions for recruitment, support, and completion programs with proven track records of success, such as: systematic consideration of a student’s environmental context in admissions assessments; on-campus supports, including academic counseling, tutoring, and emergency financial aid; and use of data analytics to restructure programs and redesign courses (e.g. flipped classrooms). Attach consequences for institutions that continually and despite repeated warnings enroll low percentages of Pell students on the access front or lag on completion either overall or in terms of closing gaps, such as: conditioned board of trustee reappointment; college president appointment and compensation; financial audit; and limitations on non-academic, new construction capital funding (e.g. residence life, athletic facilities, etc…).

Pros: There’s a strong civil rights coalition that backed the K-12 Every Students Succeeds Act (ESSA) that can be expected to back a higher ed accountability proposal. Examples abound of successful institutions on the equity front as well as lagging peers. Recommended proposal avoids the testing issue, which is not present in higher ed in nearly the same way it is in K-12.

Cons: Will be smeared as NCLB for higher ed. Similarly, will be criticized as first step on a slippery slope toward postsecondary teacher evaluation based on student test scores and decline in academic standards. Privately, elite institutions will claim proposal undermines commitment to scientific discovery and academic freedom. Not clear that non-financial consequences will be enough to motivate change. Opponents will claim financial consequences for institutions will be passed on to and harm students.

# # #

To me, one finding from our recent deep dive into Massachusetts public higher education has been particularly shocking. Bay State students of color are much more likely to attend a community college than the national average and much less likely to complete their degrees.

Massachusetts Black high school graduates are 50 percent more likely, and Latino graduates are nearly twice as likely as their white peers to attend an in-state community college. Yet, Black students are 54 percent less likely than their white peers to complete and Latino students are 48 percent less likely to complete an associate’s degree program within 3 years. And that’s for first-time, full-time students. Completion rates are typically much, much worse for part-time students and non-first-time students.

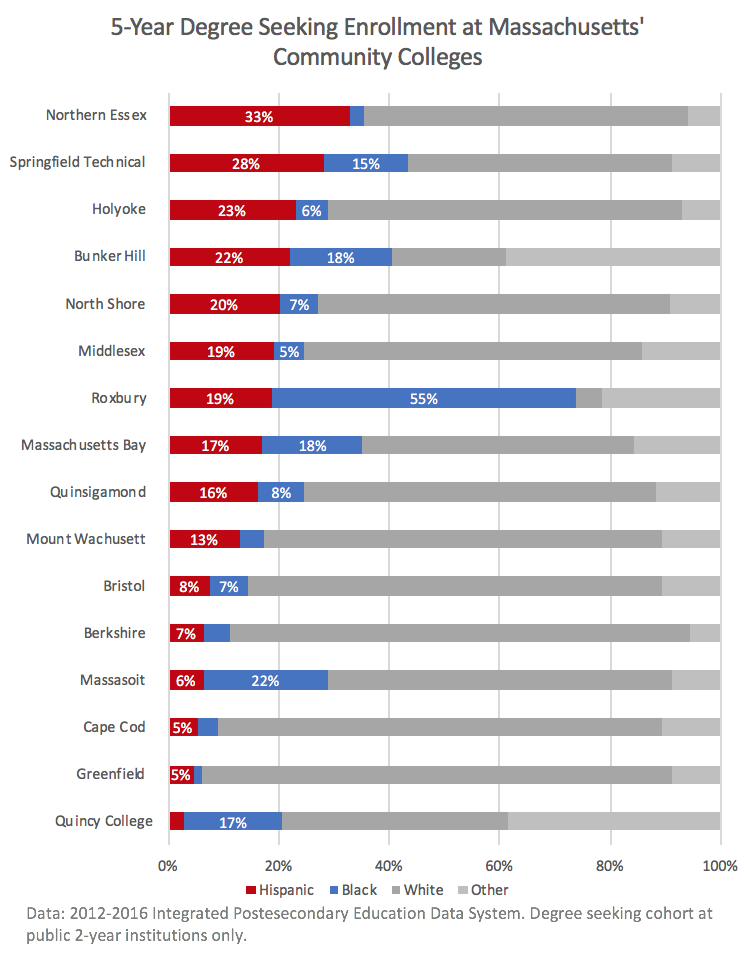

The following chart captures the racial and ethnic composition of the degree-seeking cohort by combining data from the past five years (to increase sample sizes). As is evident, different schools serve different populations, but perhaps the most important thing to recognize is how disproportionately represented students of color are, overall.

A look at the five-year average of Massachusetts’ 18-24 year-old (“college age”) population finds only 9 percent of the state’s population is Black and only 14.3 percent of the state’s population is Hispanic or Latino. Yet, when one examines Bunker Hill Community College enrollment, for example, there are over twice as many Black students, and over one-and-a-half times as many Latino students as would be representative of the state’s college-age population,

Moreover, in general, the completion rates at these community colleges are poor. Only one of these community colleges has an overall first-time, full-time degree seeking student 3-year completion rate over 25 percent — Greenfield, at 26 percent. Unfortunately, Greenfield also had the lowest enrollment rates of Black (1 percent) and Latino students (5 percent). It might as well be in Vermont.

When one looks specifically at Massachusetts’ community college Black student 3-year completion rates, no institution has a success rate above 15 percent, and for Latino completion rates, the only institution to average above 20 percent was Berkshire Community College, at 22 percent.

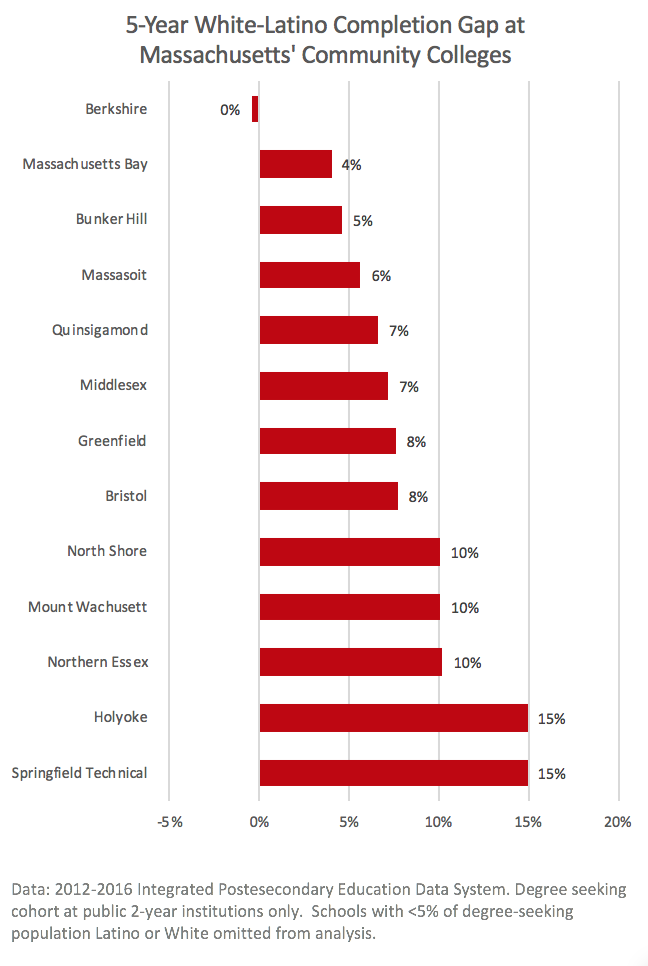

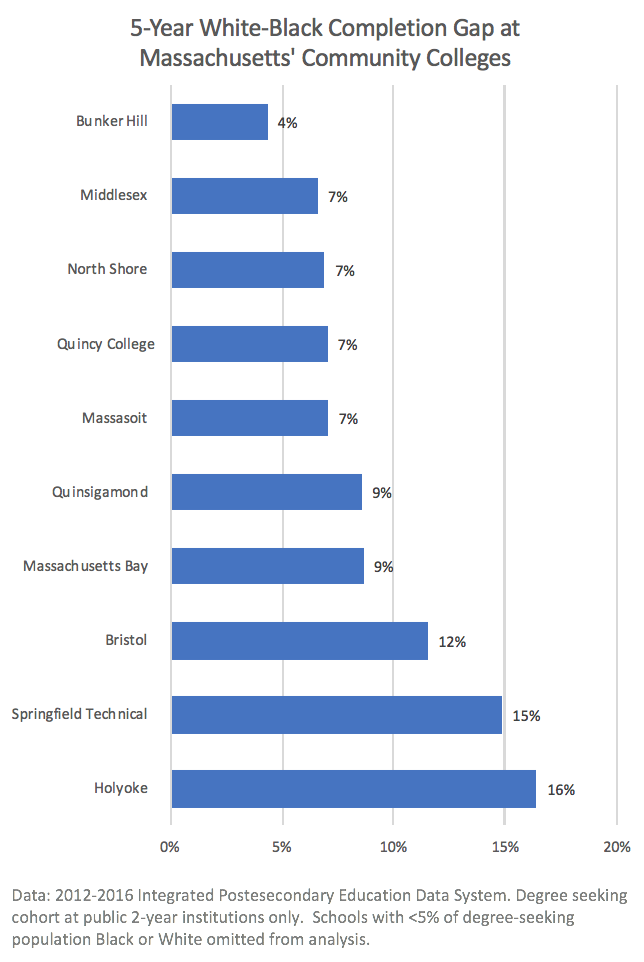

Worse still are the completion gaps facing students of color across these institutions. The charts (below) illustrate the 5-year graduation gaps between students of color and their white peers. From our analysis, it is clear that some institutions work and are more successful in closing their gaps better than others. One concerning actor is Springfield Technical Community College – which has one of the highest overall completion rates (still only 20 percent), one of the highest proportions of enrolled students of color, and yet also has some of the largest gaps between white students and their Black and Latino peers – both gaps are 15 percentage points wide. Put another way, despite high overall completion rates, a Black or Latino student at is less than half as likely as a white student to graduate from Springfield Technical.

So, what can communities and colleges do to close gaps and raise overall completion rates? Well, the single greatest predictor of college success is academic preparation. To get better results, we recommend making the MassCore college preparatory track the default track for every student, and crucially, also provide high schools and non-profit community-based organizations additional resources to provide academic support for those students who are behind. That means everything from one-on-one tutors to extended learning time during the year and over the summer. Massachusetts has a history of raising standards and providing additional aid for extra support to boost achievement. It needs to double down on that strategy in high schools.

We also recommend providing targeted state resources to community colleges and non-profits in order to provide proven supports like counseling, child-care, and transportation aid for struggling students. In return, we suggest that institutions need to be held more responsible to governments and accrediting agencies for their gaps in access and outcomes. If we give institutions additional resources to provide better services and close equity gaps, then we expect those resources to be put to good use or risk consequences ranging from altered institution leadership to repayment (potentially with interest).

# # #

For a more detailed discussion of these policy proposals, and our comprehensive college promise plan for Massachusetts, please see our recently released report: No Commencement in the Commonwealth: How Massachusetts’ Higher Education System Undermines Economic Mobility for Latinos and Others – And What We Can Do About It.

by Michael Dannenberg and Konrad Mugglestone

Education reform advocates should recognize that extending their work to higher ed is a moral imperative that also happens to present a political opportunity.

Here’s a summary of our argument:

- Education reform will fail to deliver on its goals if we do not improve the quality of higher education access, overall affordability, and student outcomes.

- A high school diploma is not enough in today’s economy. Young people overwhelmingly recognize it, accordingly pursue higher education, and all too often experience dismal results.

- There rightfully has been a lot of attention to the failings of the for-profit postsecondary education sector, and its profound impact on young and older students alike. But the higher ed reform challenge extends much further.

- Three key stats:

- Over 75% of 18-25 year olds go on to postsecondary education. They may take time between high school exit and college entry, but they go. The vast, vast majority attend community colleges and public four-year institutions.

- Some 50% of all postsecondary students drop out. There are more college dropouts than high school dropouts. And those who drop out are four times more likely to default on a student loan.

- There’s new public data. Measured over a 12-year period from initial loan assumption, there is a near 50% Black borrower default rate. There is a 23% default rate for Black bachelor degree holders. Think about that. Twenty-three percent of bachelor degree holders. Public sector reliance on individuals taking out student loans to finance higher education is DEVASTATING Black, Brown, and low-income families.

- We need high schools to do a better job preparing students academically for postsecondary training. We need less reliance on student loans (i.e. increased college affordability). And we need colleges to do a better job.

- In the K-12 education system, we don’t see students as the problem, but institutions. In the higher education system though, we hold students responsible but not institutions. That needs to change. Both groups have power over outcomes.

- Some states and colleges do a good job or at least better than others. Some do a horrible job.

- Massachusetts has the 3rdsmallest white-Black public four-year college degree completion gap and the 37th worst white-Latino gap. Why? Because Massachusetts effectively channels talented Latino students into community colleges.

- Florida State and Michigan State have the same median SAT scores, same incoming student high school GPA, and yet generate wildly different results. At Florida State, there is no degree completion gap between white and under-represented minority students. At Michigan State, there is a 41 percent degree gap between white and Black students. Only 3 in 20 Michigan State Black males graduates on time. At Florida State, it’s three times higher.

- At the University of Akron, less than 20 percent of Black male students graduate within six years of initial enrollment. (Someone tell LeBron James, who not long ago pledged $41 million to the school.)

- Nationwide, nearly 100 four-year colleges have an overall six-year dropout rate above 80%.

- The good news is that as in K-12, there are proven strategies that work.

- We see it statewide in Tennessee, at Georgia State, Cal State-Fullerton, CUNY’s Lehman College, Fort Worth Community College, Portland, Oregon Community College, etc, etc…

- Every institution of higher education can improve on access, affordability, and success metrics for disaggregated subgroups, if not overall.

- It’s the same recipe for success as K-12: “resources and reform.” You can get some improvement with either alone, but you get maximum improvement with both.

- Progressives should make sure that ‘free’ college promises aren’t delivered by politicians on the cheap. Providing new, ‘last dollar’ tuition and fee scholarships as opposed to ‘first dollar’ grants to low-income students isn’t enough. Hard-pressed middle income and low-income families need a “debt-free” guarantee that extends beyond tuition and fees. Colleges need resources to improve student outcomes, and all should be held more responsible for results.

- Bottom line — Education advocates need to think of education reform as a K-16 challenge.

- Otherwise, K-12 education reform will fail to change many lives, and we’ll squander an opportunity to use the intense interest in college affordability to leverage change in K-12, specifically high schools.

The moral outrage that animates K-12 education reform needs to be brought to higher education. Now.

# # #

For those graphically inclined and looking for more detail, see our Powerpoint presentation here.

When the public laments the closure or threatened closure of small colleges like Burlington College, formerly run by Sen. Bernie Sanders’ wife, or Sweet Briar College in central Virginia, they mourn the loss of a piece of history, a source of pride. But rarely do they ask how those colleges actually served or are serving their students. Perhaps it’s better for students that some low-performing colleges have closed, because at least now future students won’t be as likely to be burdened with a lifetime of debt from those institutions and no degree with which to obtain a good-paying job that enables them to repay that debt.

Related: Part 1: Good Bye ACICS? Watch Out, Private Colleges

Several small private nonprofit colleges that have been threatened with closure in recent years, for example, enrolled sizable numbers of low-income students, charged them exceptionally high prices as a function of their income, yet provided them with little positive outcome – namely, the college degree they were there to receive. Take a look at the data below for six randomly selected colleges that have closed or face closure.

Closing a school is a last resort and a decision that undoubtedly affects the lives of faculty, staff, and many others in the community — often for the worse. But at their core, schools are not job programs for adults. They’re institutions that are supposed to educate students with at least some minimal level of effectiveness. And sometimes, no matter how fraught the situation, closure may be best for vulnerable students.

We’ve seen this phenomenon play out in K-12 education. Over fierce criticism in Chicago, Mayor Rahm Emmanuel made the extremely unpopular decision to close 50 under-enrolled and low-performing schools. He was vilified. But research has found that nearly all of the Chicago students displaced by Mayor Emmanuel decision moved on to schools with higher performance ratings. Research is not yet available on those students’ subsequent academic outcomes, but preliminary data from the Chicago Board of Education suggests less expulsions and suspensions and higher test scores.

In New York City, Mayor Michael Bloomberg also made the divisive decision to close 29 high schools for low performance. Research there also found that displaced students ended up enrolling in higher-performing high schools. And the benefit was even greater for future students, as current middle-schoolers attended higher-performing schools and saw a 15-point increase in graduation rates compared to students in similarly low-performing schools that did not close.

We’re not sure if politically, Mayor Emmanuel or Mayor Bloomberg still think the decision to close underperforming schools was worth the opposition. But we are sure from a policy standpoint that students, particularly poor and minority students, benefitted. And in higher education, where a combination of toughened oversight from the Obama administration and state attorney generals on for-profit colleges led to the closures of some of the worst for-profit colleges – and potentially even greater, the accrediting agency that oversaw those colleges – we’re certain that students, too, have and will continue to benefit.

For college leaders beyond the for-profit sector to suspend their ethics or rationalize away predatory behavior in the name of low-income student access, but whose ultimate underlying driving motivation is to ensure the financial security of their struggling institution, is both wrong and eventually, unsustainable. Just yesterday, four small private colleges were placed on probation for financial struggles. Moody’s rating service already has estimated that the number of four-year nonprofit colleges going out of business will triple and the merger rate will double by 2017.

But if college leaders focus on actually having their students return every year and actually graduate from their institutions within a reasonable period of time, then not only would they have a much more prudent financial strategy, but they would also be providing the education, service, and ladder of socioeconomic opportunity that they profess to produce.

From a policy standpoint, the K-12 school closure experience and lessons learned from the Obama crackdown on poor-performing for-profits schools should send a clear and urgent message to all colleges: Focus on your students. Focus on your value. And focus on the outcomes you produce for your students.

In the words of one private college provost: “If you’re seeing half the students disappear after the first year, you’ve got to ask yourself what business you’re in. Because it isn’t education.”

Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner (R-IL) is holding hostage billions of dollars in state education funding. If the Democratic state legislature does not approve Rauner’s demands on tax freezes, collective bargaining, worker compensation, and inequitable school spending, he will veto the 2017 budget wholesale.

The governor is, according to Chicago Mayor Raum Emanuel, reenacting the story of Moby Dick, where Rauner is dead-set on tackling the whale, in this case State House Speaker Michael Madigan, instead of caring for the lives of the ship’s passengers, Illinois citizens. Meanwhile, Rauner and state Republicans are dismissing the mayor’s call for desperate financial help for Chicago Public Schools as a bailout.

The state, by the way, has been operating without a budget since last July.

If this tactic reminds you of the brinksmanship strategy employed by Ted Cruz, the Tea Party, and Congressional Republicans with threatening to default on the national debt if Democrats didn’t repeal Obamacare, well, it should. Cruz and Congressional Republicans threatened the bond market. Rauner is using the future of Illinois children, among other needy populations, as his political pawn.

How despicable.

In education policy, much research has been prepared on the idea that schools must be accountable to their students. In K-12, schools must track students’ academic outcomes annually and focus attention and interventions on low-performing subgroups of students and schools. In higher ed., similar discussions are mounting on the need for colleges to be accountable for student success both during their academic careers and after graduation.

But this budget impasse makes one thing very clear: So too must lawmakers hold up their side of the equation.

Democrats in the legislature argue that the budget process should not be about promoting policy reforms, but about distributing sufficient and equitable funding for social services, including the state’s K-12 and higher education systems.

As the Illinois Constitution says:

“The state shall provide for an efficient system of high quality public educational institutions and services. The state has the primary responsibility for financing public education.”

So much for respect of the rule of law.

Currently, Illinois is ranked dead last out of all states for education spending from the budget – only a little over a quarter of dollars spent on education comes from the state, with most coming from local property taxes. The state, in fact, has been defunding education by a total of $1.4 billion dollars since 2009!

While politicians at the state capitol argue, the President of Chicago State University, Thomas Calhoun, has planned massive layoffs and a shortened school year.

School districts across the state are worried they won’t open on time.

At a time when progress was being made on postsecondary education enrollment, students are losing hope in their state schools, forcing them to look out-of-state for college, if at all. K-12 schools will be forced to run on reserve funds and programming as well as social services could be ceased.

How can we approach education policy by promising students funding in exchange for hard work and good grades, if we can’t hold up our side of the bargain?

In the short-term, partisan quarreling has resulted in a last-minute stop-gap measure signed by Gov. Rauner that funneled $600 million to help struggling higher education institutions. But this short-term measure only lasts until the end of the summer, keeping state colleges and universities on edge for future prospects.

More than a dozen superintendents sent a letter to the governor’s office, expressing their frustration with the political games played in Springfield taking pertinence over the lives of schoolchildren. This may fall upon deaf ears, however, as the legislative session has ended for the summer. But lawmakers have “promised” to continue working after the session ends and that they’ll consider a short-term solution in the coming weeks.

If not though, the fight continues in September when lawmakers gather again.

Lawmakers must remove themselves from their comfortable political corners, stop jockeying for position, and carry out their constitutional obligation to fund Illinois’ future.

It will take several years for the effects of this battle to wear off and it will no doubt affect disproportionally low-income families – especially in Chicago — who will be forced to bear the brunt of any negative financial ramifications.

As the Chicago Tribune’s Eric Zorn notes, “It will take courage on the part of legislators to get Chicago off that list of most disadvantaged schools and offer a better future to all kids in Illinois growing up in property-poor districts.”

As advocates for education reform, it is our job to look out for these children’s lives, and to provide a voice for those without.

Education is at the foundation of making those lives better.

Illinois state lawmakers should do their jobs, provide funding for education, and advance school reform and improvement. Do not hold innocent students’ lives hostage.