Every state in the U.S. has either ordered or recommended the closure of public elementary and secondary schools and at least a dozen have ordered or recommended that schools remain closed through the end of the academic year. To help districts stem the dramatic loss of learning time for students, most states are providing guidance and support as they embark on an effort to deliver long-term remote instruction.

As advocates interested in preventing the exacerbation of achievement gaps in this time of crisis, we believe it is important to evaluate what states are doing and how quickly they have been able to mobilize in the face of unprecedented interruptions in classroom learning. Our updated analyses of all 50 states and Washington, D.C., show that:

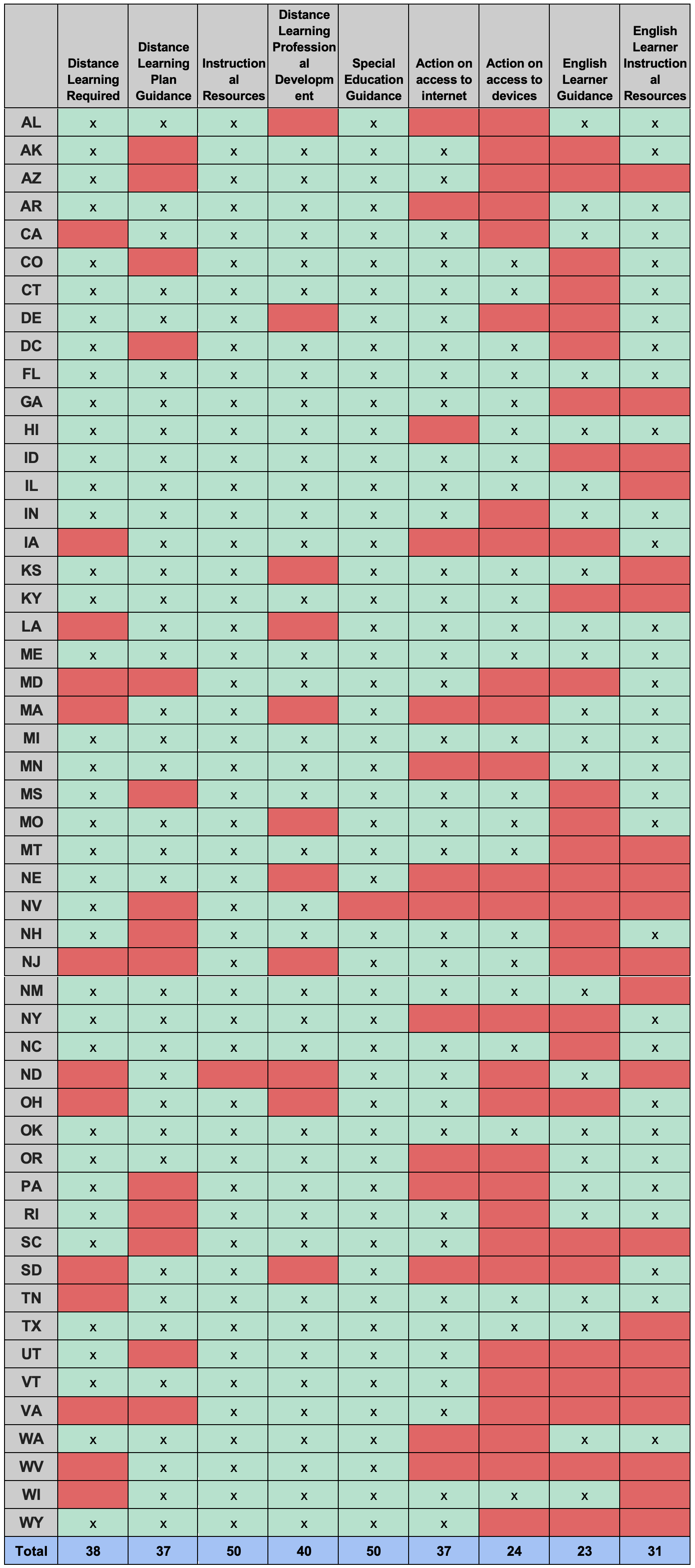

- Nearly all states—49 and DC—are providing access to instructional resources for teachers and families.

- 49 states have issued guidance on addressing the needs of students with disabilities during school closures. Many of these have taken the form of Q&A documents, addressing specific questions states are receiving from district officials. Alaska has been hosting daily webinars to answer questions related to SWD and COVID-19.

- 40 states are also providing teachers with access to accelerated professional development opportunities, including how to engage students online and how to prevent being “zoom-bombed.” GaDOE has created two online courses for teachers on distance learning, with a third on synchronous learning coming soon.

- Only 38 states are currently requiring all districts to provide distance learning. For example, California, which enrolls more than 10% of our nation’s students, has declared that “The transition to distance learning, including when instruction and grading resumes, if it has been halted, is a local determination.”

- 37 states have documented actions they are taking to improve home access to the internet or provide guidance to districts on how to do so. Idaho, for example, has a list of over 30 options for districts and families to access no/low-cost internet, while South Carolina has a map showing wifi hotspots around the state (many on schools buses they’ve deployed in low-access neighborhoods).

- 31 states have included instructional resources and digital accessibility options for English Learners (EL). However, only 24 states have issued any specific guidance to districts about how to best serve EL during school closures. For instance, Minnesota has a section of their district learning plan template dedicated to considerations for EL, along with a link to separate guidance and instructional resources specific to EL.

- Only 24 states have focused on ensuring that students have internet-connected devices that they will need to access digital resources. Washington, DC, for example has promised that “all high school students without access to a device at home will now receive one.” Those states late to the game on this are likely to be shut out as districts around the country have already reported difficulty and delays when ordering new laptops.

When states are able to conduct needs assessments and present districts with guidelines on how to develop distance learning plans and deploy necessary resources, they can help level the playing field between and within districts and narrow the digital divide. North Carolina has a consistently updated website devoted to distance learning, with guidelines for districts developing comprehensive plans, strategies for schools deploying technology, a series of trainings for teachers, and instructional resources for building remote lesson plans. By contrast, three states published little guidance to districts on its Department of Education website, apparently leaving districts largely to their own devices.

In light of state guidance, or in some cases in spite of the lack thereof, districts are also forging ahead with a range of remote learning efforts, which are constantly evolving. A Brooklyn parent told us that after the first week in which parents took the lead on instruction and few Black and Latinx students participated, in week two “with teachers leading the video meetings, with free Internet having been offered by Spectrum, and with the delivery of several hundred thousand laptops/tablets across the city to kids who needed them, both my kids’ classes are at 99% participation.”

For a more comprehensive look at district responses, check out the Center on Reinventing Public Education, which has an ever-growing database of individual district approaches to distance learning. The 74 has also profiled efforts in districts around the country including NYC, Los Angeles, and Guilford County, NC.

With regard to state action on distance learning, we’re not saying here that fast is necessarily good or that slow is inherently bad. Each state faces different challenges and in many instances states and districts may be proceeding more slowly because either they or the families they serve lack the capacity necessary to fully carry out homeschooling. We are presenting this update in the hope that states, districts, policymakers, educators, and parents can learn from each other about how best to serve as many students as possible as effectively as is practicable.

We will continue to provide updates in the coming days and weeks to include the most up-to-date information on state initiatives.