Not long after the initial shock of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe, people who work in higher education and college admissions started thinking about the potential impact of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization on college enrollment. While the impact of banning or severely limiting abortion will fall on those who live in the states that have restrictions and those who are likely to attend a local college or no college at all, it is worth asking whether the prospect of being denied access to an abortion or a lack of appetite for living in a state that denies people autonomy over their own bodies could inspire a large number of students to eliminate colleges and universities from their application lists and, thus, provide an impetus for rescinding restrictions?

The short answer is probably not.

Just 21 percent of freshmen go out of state for college. A substantial portion of the population that goes out of state may not take a state’s abortion law into consideration in deciding where to apply or enroll, either because they believe it is not relevant or because they have the resources to return home to get an abortion. Since tuition at private institutions and for nonresidents at public institutions tends to be higher than it is for those who attend in-state colleges, students who cross state lines for college tend to be wealthier.

The longer answer is that, even if the impact of abortion laws is unlikely to create major shifts in the college enrollment landscape, restrictions could have a significant impact on two kinds of institutions in states with strong abortion laws: public universities that rely heavily on out-of-state students from states without abortion restrictions and private universities that underserve their states’ students and also recruit heavily from more liberal states. Bad abortion laws and bad recruitment policies could very well lead to a loss of students and of revenue.

For the past two decades, most states have decreased the amount of direct financial support they provide to public institutions, which has driven colleges and universities to increase the cost of attendance. Student tuition revenue is responsible for half the cost of four year colleges or more in over two-thirds of the states. In eight states, students cover more than 70% of the cost.

The map below connects state funding for four year colleges with likely abortion policies. In liberal states, on average, the state provides 52% of the revenue for public four year colleges, while conservative states, on average, only provide 45%. It should be noted that some of the states that provide the most support for four year education, like Wyoming and Georgia, have strong restrictions on abortion, while some of the states that do the least, like Vermont and Colorado, provide the strongest protections for abortion rights.

Flagship universities in states with weak state funding and stringent abortion laws are the public institutions most likely to be hurt by this combination of terrible policies. These universities, which often have strong research programs and prominent NCAA Division I teams, might seem to be in an enviable position, since they can attract students from across the country or even the world. In some states, where public support of education is weak, the flagships have become dependent on out-of-state students to cover their costs. In Alabama or West Virginia, for example, more than half the freshmen at the flagships come from out-of-state.

Flagships in conservative states do not, of course, just enroll students from conservative states. Jon Boeckenstedt, the vice provost for enrollment management at Oregon State University, recently used IPEDS data on freshmen migration patterns in 2018 and 2020 and a New York Times analysis of which states are likely to impose restrictions on abortion rights to identify what kinds of states students are migrating from and to at over 2000 institutions. Using his data, I have narrowed my analysis down to four year colleges in states that the Washington Post identified as likely to impose abortion restrictions. The results show that some institutions might face real challenges to their revenue.

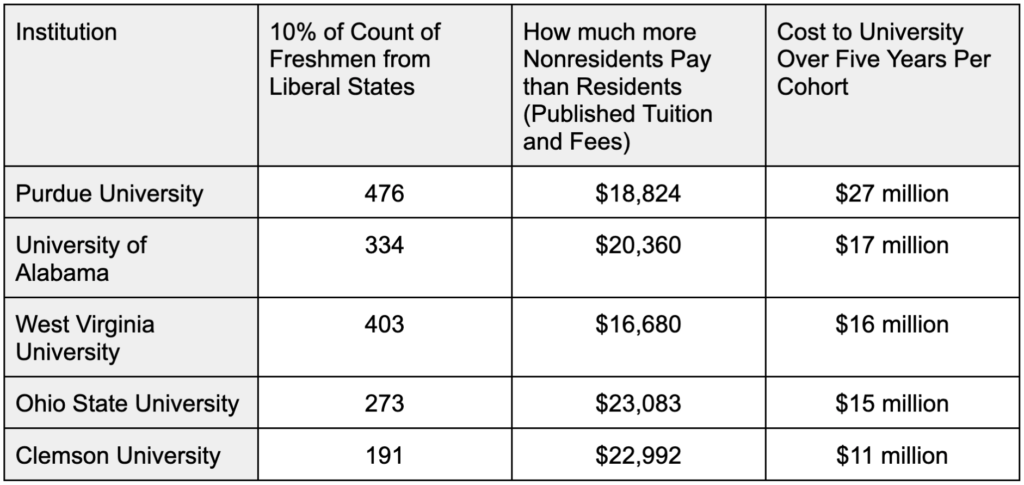

At the University of Alabama, more than three-fifths of freshmen come from out of state. Just over a quarter of freshmen come from states without substantial barriers to reproductive rights. At the University of West Virginia, 45 percent of all freshmen are from liberal states. At the College of Charleston in South Carolina, a third are, and at Purdue University in Indiana, 28 percent are. All those students will not, of course, opt out of applying to or enrolling in these prominent institutions, but even a relatively small drop of 10% in their number could have a substantial effect since the premium they pay as nonresidents can amount to more than $20,000 per year—which adds up even more over the four to six years most students take to graduate.

It is not just public universities in conservative states that may suffer for their reliance on out-of-state students. Some private colleges could also pay a high price for their failure to recruit and enroll students from their own state. While underfunded public colleges at least have some justification for chasing out-of-state students who pay more than residents, private colleges who under-enroll local students bear the responsibility for electing to take a path that will put their institutions at risk.

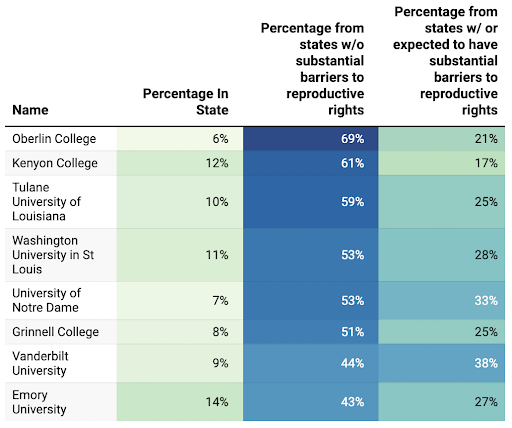

The enrollment challenges could be especially high for highly ranked colleges and universities known for enrolling very liberal students from liberal states. In 2018 and 2020, just 6 percent of the freshmen at Oberlin College were from Ohio, and almost 70 percent were from states with liberal abortion policies. Oberlin’s students are well known for their political activism, which could translate into an enrollment crash for them in the years to come. Grinnell College in Iowa and Tulane University in New Orleans are not quite as extreme in their neglect of students from their home state, but they too could experience serious shocks as a result of their own bad recruitment policies and their states’ worse abortion policies. Even a Catholic university like Notre Dame cannot expect to be spared by students refusing to put themselves at risk by enrolling there. After all, a majority of American Catholics believe abortion should be legal.

While it might be tempting to say to these universities, “You get what you deserve,” students from low- and middle-income households will pay a price there too. Even though the private institutions in the table above all have large endowments, a decline in full-pay students from liberal states who very understandably do not want to move somewhere that does not recognize their reproductive rights could lead to a decline in financial support for students who need it. Tulane already admits the smallest share of freshmen with Pell Grants in the nation, and Oberlin and Kenyon routinely rank near the bottom in enrollment of low-income students, so it is hard to imagine how it could get worse there, but it could. If public and private institutions in conservative states depend on revenue from liberal states, they may need to cut the number of students they admit with financial need, reduce the amount of financial support they provide, or both.

In this dark moment in American history, the universities and colleges that are likely to be hurt by this collision of two bad policies—taking away reproductive rights and relying heavily on out-of-state recruitment—could, however, become advocates for reversing them both.

###

The searchable table below uses data from Higher Ed Data Stories to identify the portion of freshmen in 2018 and 2020, combined, who were in-state students, students from states that are not expected to place restrictions on abortion, students from states that are expected to place restrictions on abortion or already have, and foreign students, as well as the number of freshmen enrolled. It only includes four year colleges in the restrictive states, as they are much more likely to enroll students who move to and live in those states.