A new paper about who gets into some of the most selective colleges and universities from the Opportunity Insights group contains stunning findings about who benefits from legacy admissions and just how much harm legacy preferences do to social mobility and access at the nation’s most selective universities and colleges. We strongly recommend reading the whole 125-page paper, but just in case you don’t have the time, Education Reform Now pulled out some of the most significant revelations from the paper. Perhaps none of them are surprising, but they are still pretty shocking.

1. There are a lot of really rich people at Ivy-Plus Colleges.

Students from the richest 1% of households make up 15.8% of students at Ivy-Plus colleges (i.e., the Ivy League, Stanford, University of Chicago, MIT, and Duke).

2. The biggest reason there are so many rich people at Ivy-Plus colleges is legacy admissions.

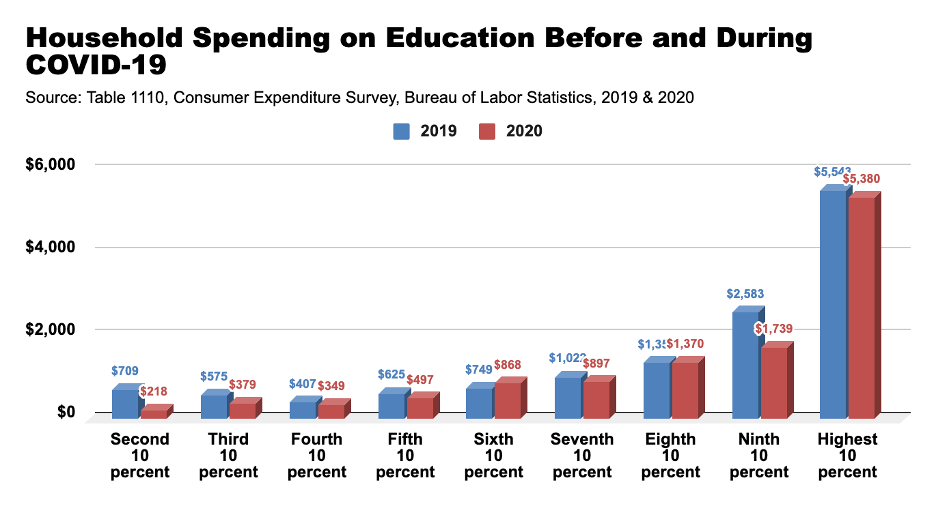

Students from the 1% are 55% more likely to be admitted to an Ivy-Plus institution than a student from the middle class (incomes between $83,000-$116,000) is. Applicants from rich families tend to be well-prepared academically, which is no big surprise given the fact that wealthy, well-educated parents have the money and the know-how to make sure their children have all the academic resources they need. Consider this chart of household spending on education before and during COVID we created using federal survey data.

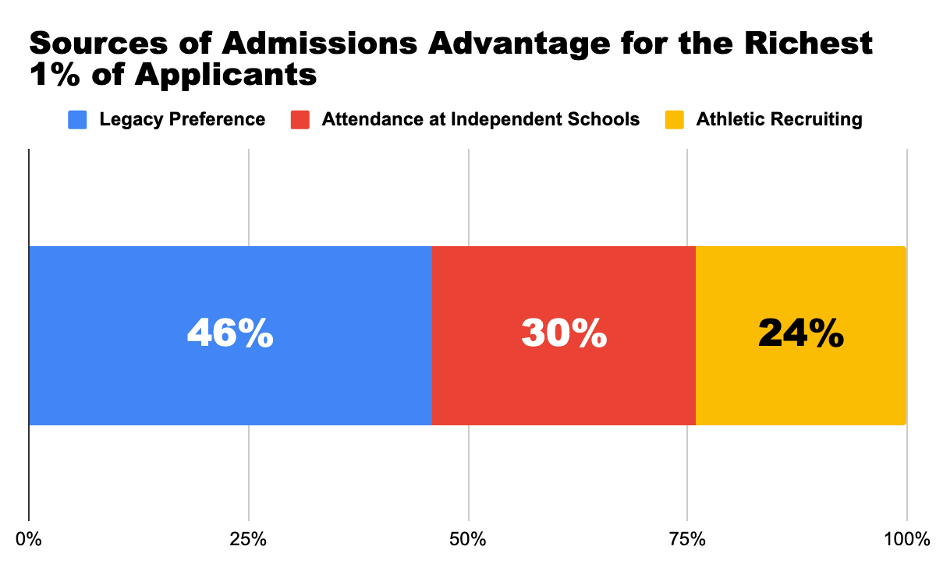

The reason so many students from the richest 1% get into Ivy-Plus colleges is not really academic, however. The Opportunity Insights paper compared students who were academically similar and found that the 1% were still more likely to get into an Ivy Plus college thanks to three factors: legacy preferences, athletic recruiting, and non-academic qualification that correlated strongly with attending expensive private high schools, often called independent schools. The only Ivy-Plus college that does not provide a legacy preference is MIT. At all the others, however, being a legacy provides a large advantage.

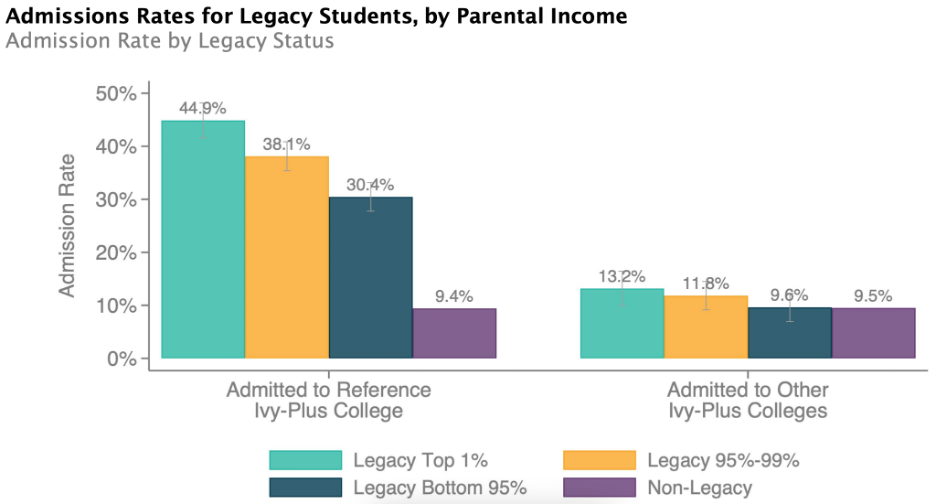

3. All legacies have a greater likelihood of getting into an Ivy-Plus college, but the richest legacies have an even better chance.

If you compare legacies from families below the 90th percentile for income they are 3 times as likely to be admitted as peers with comparable academic credentials. But if you look at legacies from the top 1%, they are 5 times as likely to be admitted as the average applicant with similar test scores, demographic characteristics, and admissions office ratings.

4. When a legacy at an Ivy-Plus college applies to other Ivy Plus Colleges, they are two-thirds less likely to be admitted.

Colleges like to say that the reason they admit so many legacy students is that they are such strong applicants. That sounds plausible, as we noted in point one, since highly educated, rich parents are likely to invest money in their children’s education and can pass on their own learning and understanding of how elite education works. The problem with this defense of legacy admissions is that when you look at legacies’ success rate at getting admitted to other highly selective colleges, their advantage largely vanishes. If legacies are so brilliant and over qualified, why are they not getting in everywhere at the same rate?

Source: Opportunity Insights, 2023

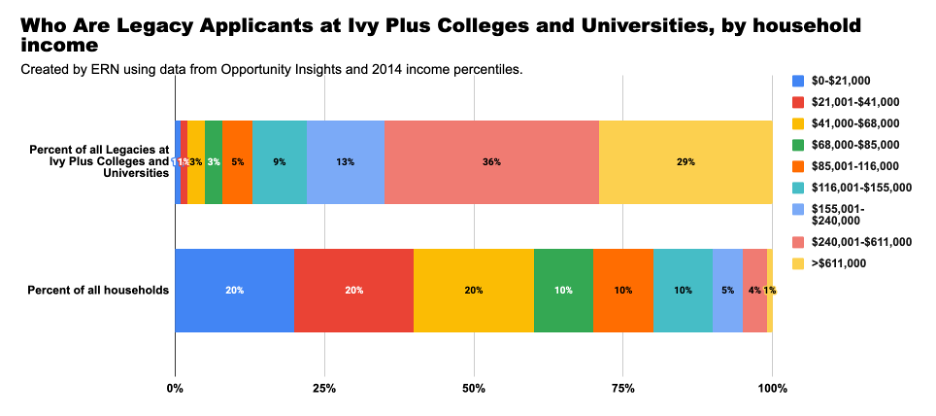

5. Most legacies come from very rich families.

Another of the weak defenses made for legacy preferences is that civil rights groups and advocates for college access and equity are trying to eliminate legacy preferences just as colleges and universities are growing more diverse. Leaving aside for now the bizarre notion that the way to make a corrupt practice less corrupt is to marginally expand the number of people who benefit from the corruption, the Opportunity Insights paper and a companion piece in the New York Times make it clear who the beneficiaries of legacy admissions are: rich people.

- 65% of legacies who attend Ivy-Plus colleges come from the richest 5% of American households by income.

- Just 5% of legacies who attend Ivy-Plus colleges come from the bottom 60% of American households by income.

We have long known that providing a legacy preference works against diversity, social mobility, and basic fairness. These new findings only make that point clearer.

College presidents and boards can no longer ignore the facts about legacy admissions. They have until the fall to announce that they will no longer use a legacy preference–as more than 100 colleges have in recent years–or they will essentially be telling students, families, and the nation that their commitment to diversity goes no further than words.