An Update on the Most Despised Practice in College Admissions

Updated September 30, 2024.

A shrinking number of colleges and universities are clinging to the practice of passing an admissions advantage along the bloodlines of the nation’s richest families, so states are making them do the right thing.

Our country was founded on the principles that opportunity should be open to all, not just those who inherit it from their parents, and that merit should determine success, not lineage. A shared belief in core American values underlies the widespread opposition to legacy preferences. Providing an inherited advantage to the relatives of alumni in the college admissions process is unfair and gross, and just about everybody knows it:

- Three-quarters of Americans, including a slightly larger percentage of Republicans than Democrats, think that colleges and universities should not consider who an applicant is related to as part of the admissions process.

- At highly selective colleges such as Harvard, Cornell, Georgetown, and Princeton, most undergraduates, including legacies themselves, oppose passing an admissions advantage along family bloodlines.

- Seven out of eight leaders of admissions offices do not believe that legacies should have an advantage in the admissions process.

- Since 2015, almost 400 colleges and universities have stopped considering legacy status in their admissions process.

That last number is based on Education Reform Now’s analysis of answers to the Common Data Set for academic year 2015-16 and answers to the Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data Survey (IPEDS) for academic year 2022-23. We expect the number of colleges and universities dropping their consideration of legacy status to grow even larger with the next release of IPEDS data. That data, released this fall, will reflect survey answers gathered after the Supreme Court’s decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and UNC (SFFA) ended the consideration of race in admissions decisions. The Court’s majority opinion not only sparked a national conversation about legacy admissions but also led to more than a dozen prominent universities ending their use of birthright advantages, including Wesleyan, Occidental, Carleton, NYU, Boston University, the University of Pittsburgh, Virginia Tech, and Carnegie Mellon.

The Moral Failure of Highly Selective Colleges

In the summer of 2023, it felt like many highly selective institutions would deliver on their lofty statements promising to protect diversity on campus by getting rid of the most egregious example of an admissions practice that protects the privilege of very rich, white students.

That did not happen.

Even as more and more institutions have quietly dropped legacy preferences, the wealthiest and most selective colleges in the nation have dug into their commitments to laundering the privilege of the nation’s most advantaged students. Several highly selective universities, including Yale, Brown, and Princeton, have decided it is perfectly fine for them to keep providing a leg-up in admissions to the children of alumni through legacy preferences, even after research showed that the single biggest driver of the richest one percent’s enormous advantages at Ivy Plus colleges comes from legacy preferences. The presidents and board members of almost all the nation’s highly selective colleges seem to believe that it is not enough for the children of their alumni to have parents with the financial and educational resources that come with graduating from an elite institution. They also believe that these students deserve one more advantage: an edge in admissions decisions.

The Fight to End Legacy Admissions, 1988–2024

If colleges refuse to voluntarily stop passing admissions advantages along family bloodlines, they may soon be forced to by legislation. While attempts to curb legacy admissions go back more than two decades, in the past few years, there has been a flurry of activity by legislators and other policymakers to end the most hated practice in college admissions (all information below is as of September 30, 2024).

- In 1988, Senator Bob Dole (R-NE) asked the Department of Education to determine the legality of legacy preferences, which he likened to a “caste system,” after the department’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) found that legacy preferences helped explain the low enrollment rates of Asian Americans at Harvard.

- In 2003, Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA) introduced a bill that would require universities to publish data on the racial and socioeconomic composition of legacy enrollments.

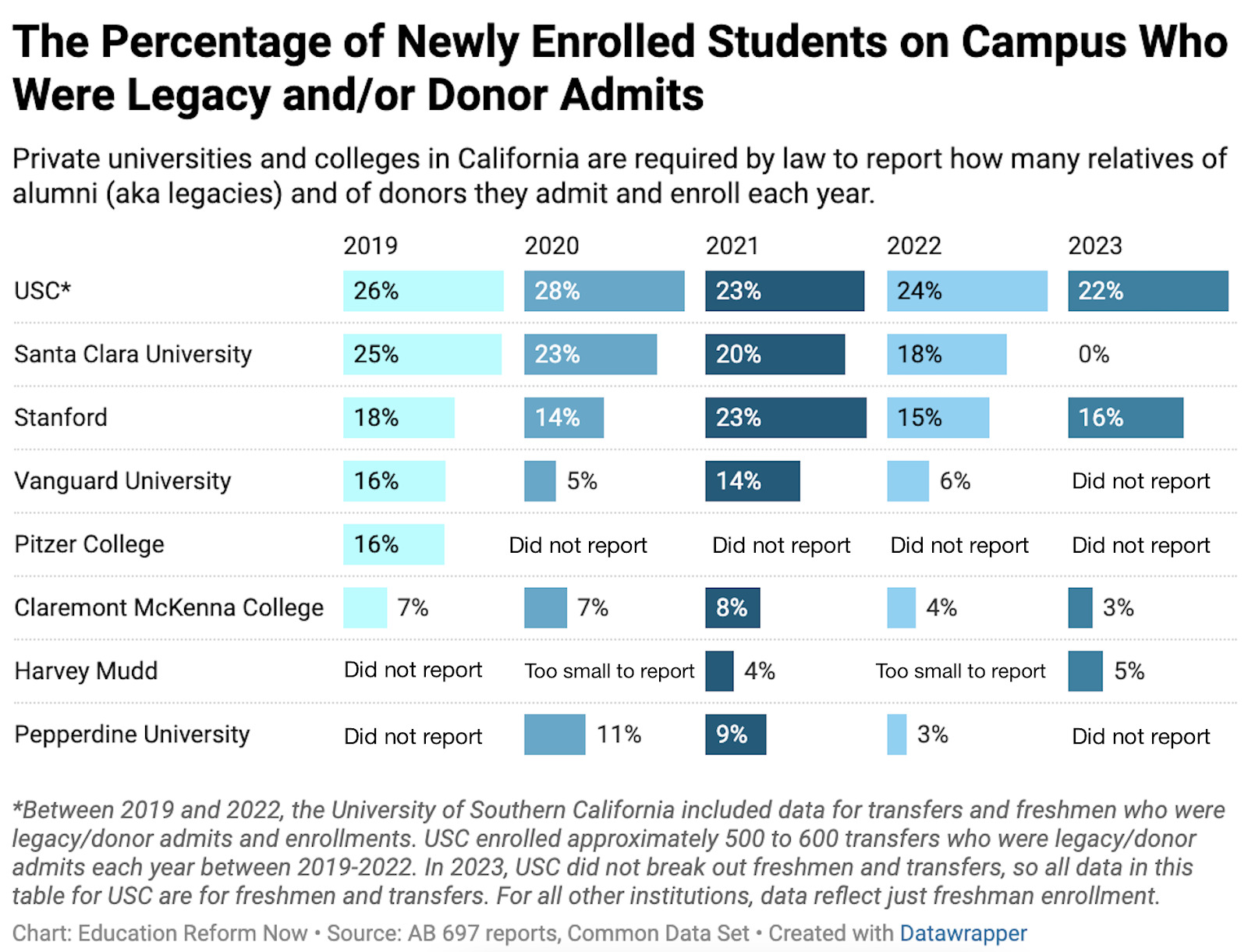

- In 2019, California passed a bill requiring colleges that provide an advantage to relatives of alumni to report how many legacies they admitted and enrolled every year until 2023. The law has now expired.

- In 2021, Colorado became the first state to ban legacy preferences at public universities.

- In 2022, Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR) introduced the first federal bill to ban legacy preferences at all public and private institutions in the United States. The bill was reintroduced in 2023 and gained several co-sponsors, but it has not advanced.

- In 2023, Massachusetts introduced a bill to ban legacy preferences at private and public institutions. The bill was advanced by the Joint Committee on Higher Education, but it has not received a floor vote despite full Democratic control of the legislature. The formal legislative session is over.

- In 2023, New York introduced a bill to ban legacy preferences at public and private institutions. The bill was reintroduced in 2024 but was not given a floor vote despite full Democratic control of the legislature. The legislative session is over.

- In 2023, Senators Todd Young (R-IN) and Tim Kaine (D-VA) introduced a federal bill to ban legacy admissions at public and private institutions. It was notable because it was a bipartisan bill, which speaks to the agreement among all Americans that legacy preferences are unfair and unpatriotic.

- In 2023, Democratic and Republican members of Congress, the Secretary of Education, and President Biden called out legacy preferences for, in the president’s words, “expand[ing] privilege instead of opportunity.”

- In 2023, the OCR began investigating complaints against both Harvard and Penn to determine whether providing a legacy preference violates Title VI of the Civil Rights Act. No findings have been released.

- In 2023, the Department of Education released the results of its first IPEDS admissions survey asking institutions whether they consider legacy status in their admissions process. It showed that hundreds of institutions had quietly stopped treating legacy status as a relevant factor in admissions.

- In 2024, Virginia banned legacy admissions in public institutions. The votes were unanimous in both houses of the legislature, and the bill was signed into law by a Republican governor.

- In 2024, Maryland became the first state to ban legacy preferences at public and private colleges.

- In 2024, Illinois banned the use of legacy and donor preferences at all public universities.

- In 2024, Connecticut introduced a bill to ban legacy preferences at public and private institutions. It was advanced by the higher education committee, and, after being amended into a transparency bill requiring institutions to share data on legacy admissions, passed in the Senate. The bill was not given a vote in the Democratically controlled House. The legislative session is over.

- In 2024, Minnesota introduced a bill to ban legacy preferences at private and public institutions. The bill did not advance after its introduction. The legislative session is over.

- In 2024, Rhode Island introduced a bill to ban legacy preferences at private and public institutions. The bill did not advance after its introduction. The legislative session is over.

- In 2024, California passed a law to ban legacy preferences at all private colleges and universities. It passed unanimously in the Assembly in May, passed in the Senate in August, and was signed into law by Gavin Newsom on September 30, 2024.

- In 2024, the Washington, D.C. State Board of Education passed a resolution calling for the end of legacy admissions in the district’s private and public colleges.

- In 2024, the group Class Action began organizing students and alumni to ban legacy admissions at highly selective universities across the nation.

Banning Legacy Admissions Properly

It will be very surprising if more states do not introduce legislation to ban legacy admissions. As more states pass bans on legacy preferences, it will be important to get the laws right so colleges and universities can follow them and authorities can enforce them.

The existing laws addressing legacy preference do not meet this bar because the definition they use leaves too much room for interpretation. They define legacy preferences as giving preferential treatment to applicants related to alumni, which sounds fine but leaves the interpretation of “preferential” entirely in the hands of institutions. Some college admissions officers have defended legacy status as “only a tiebreaker” among highly qualified candidates, and not preferential. This claim is ridiculous, since there are so many highly qualified applicants to highly selective colleges that the admissions process essentially comes down to tiebreakers.

Because the existing laws on legacy preferences do not clearly define what is legal and what is not with respect to legacy preferences, it is difficult to identify when an institution has violated the law. A case in point is California’s legacy and donor admissions transparency law, A.B. 697, which went into effect in 2019 and expires this year. The law required colleges that “provide any manner of preferential treatment in admission to applicants on the basis of their relationships to donors or alumni of the institution” to report annually how many applicants in these two categories were admitted and enrolled.

It was a good law, but it has not been as effective as it could have been because, quite simply, some institutions chose to ignore it. Pitzer College, for instance, reported legacy data in the first year the law was in effect but stopped in the second year. When I inquired about this in 2021, an admissions director told me:

“We spent a lot of time talking through this question within our office and our institutional research office. We thought the question was not worded well, and I don’t think the higher ups were fully comfortable with how they’d answered it previously. Seeing how our peer institutions were answering the question in [the] previous year and working with IR clarified some things for us, and that’s how we answered the question this year.”

It is important to note that in 2022, Pitzer College reported to the U.S. Department of Education that they do in fact consider legacy status (see under “Admissions Considerations”). We have identified 17 institutions in California that indicated to the Department of Education that they consider legacy status but told the California legislature they do not.

Even more confusing was this year’s report from Santa Clara University. From 2019 to 2022, Santa Clara reported admitting roughly 1,200 legacy/donor applicants per year on average and enrolling about 300 of them. This year, the Jesuit university reported admitting just 38 legacy/donor applicants and enrolling zero. Those numbers are hard to believe or even make sense of: not one single student in the freshman class at Santa Clara last year was a legacy?

I reached out to Santa Clara to ask if some mistake had been made. It had not. Much like Pitzer, they had redefined what it meant to provide a legacy preference:

“In previous years, Santa Clara University had complied with the AICCU AB 697 reporting requirement by including the number of students who were admitted, enrolled, or matriculated whose files indicated they had an alumni or donor affiliation. We subsequently learned that that was a broader interpretation than the legislation intended. The legislation calls for reporting on the subpopulation of applicants who were provided any manner of preferential treatment.

The current number of students listed in our AICCU AB 697 reporting represents the number of donor- or alumni-affiliated students whose admission files were tagged as having received an external recommendation for admission. The recommendation could have come from an alumnus, trustee, donor, professor, or other person. None enrolled or matriculated.“

When I asked a representative of Santa Clara who they told them they had been applying a “broader interpretation than the legislation intended,” she explained, “Following consultation with the Association of Independent California Colleges and Universities [AICCU] and a critical review of our processes, we determined that only a small group of applicants was receiving differential treatment.” It was not the California legislature who told them how to interpret the law; it was the AICCU, which represents the interests of private colleges and universities in California. In the absence of a clear definition of what it means to provide a legacy preference and of a mechanism for enforcement, it is no surprise that some institutions are opting for an interpretation–even an utterly absurd one–that makes them look better in the public eye.

It is no surprise, but it is a red flag for future legislation banning legacy admissions. We need clearer language and definitions.

Let us assume that these differences between what some private colleges in California are telling the state legislature and what they are telling the federal government are not acts of bad faith or willful defiance of the law but products of genuine confusion over whether they provided preferential treatment or “consider legacy status,” which is what IPEDS asks them.

There is also evidence of confusion in the responses given by colleges and universities to the legacy question in IPEDS. The Department of Education found that 579 institutions consider legacy status, but that number is inflated not only by the presence of institutions that are not four-year colleges or that operate under open admissions (i.e., if you pay the tuition and fees, you can attend) but also by confusion over what “consideration” means in this context.

- Legacy preferences are unlikely to have any impact on admissions at for-profit, two-year, master’s, or certificate programs, but 37 institutions of these types indicated that they consider legacy status.

- There were 227 colleges that admitted 75% or more of their applicants and also indicated that they considered legacy status in their admissions process, even though that consideration is highly unlikely to affect admissions decisions at these institutions.

- Three public Colorado universities reported that they consider legacy status, even though legacy preferences are banned at public universities in Colorado.

Clearly, there is some confusion over just what constitutes providing a legacy preference. Legislation banning legacy admissions needs to provide a clear definition that will make it easier for colleges to follow the law and for states to enforce it.

A legacy preference should be defined as including information about where an applicant’s relatives went to college in the materials that admissions readers look at during the admissions process.

Colleges may still ask applicants where their relatives went to college, but they will not be allowed to include that answer in the materials seen by admissions officers. This idea essentially does for legacy status what the Supreme Court’s decision in SFFA did for information about race/ethnicity in admissions materials. The only way to be legacy-blind is to redact that information. Using this definition has the added benefit of making it possible to enforce a ban since an admissions office’s materials could be audited if there is suspicion.

Here is an example of the language we suggest using for legislation:

When deciding whether to grant admission to an applicant, a public institution of higher

education shall not consider the applicant’s familial relationship with a person who attends or attended the institution. A public institution of higher education shall not include in the documents that it uses to consider an applicant for admission any information that discloses the name of a college or university that any relative of the applicant attended.

This same approach could be applied to donors. Legislation would require institutions to leave any information out of an applicant’s file that indicates whether and how much money an applicant or their family member has donated to a college or university.

What Happens Next

The United States is clearly moving in the direction of eliminating legacy admissions. Over the next few years, we can expect legacy admissions to become increasingly rare and join the list of bizarre, shadowy rituals practiced by elites that are understood by few Americans and benefit even fewer, like cotillions or insider trading. Whether pariah status will provide enough pressure to lead university presidents and board members to end legacy admissions may become a moot point due to legislative action at the state or even federal level or an OCR finding that legacy preferences do indeed constitute a civil rights violation. It may take some time, but it’s clear that time is up for legacy admissions.

This post has been modified since its original publication to reflect Santa Clara University’s response to out inquiry about the change in their reporting and to include updated information on legislation in California.