We have been tracking enrollment outcomes at highly selective colleges and universities for the past month (link to the tracker). With adequate enrollment data on the first-year class (the Class of 2028) from 37 institutions, we were able to do some preliminary analysis, which led to five findings about the impact of the Supreme Court’s decision in Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA), which banned institutions of higher education from considering race as one among many components in their admissions decisions. We made five findings:

- Finding 1: The variety in institutional data reporting needlessly complicates the analysis of the impact of the SFFA decision on college enrollment.

- Finding 2: The number of universities that saw demographic shifts this year was unusual, but the sizes of the demographic shifts at many institutions were not out of line with previous years’ shifts.

- Finding 3: The share of students who identify as Black/African American declined significantly at most highly selective institutions. The shares of other demographics mostly stayed flat or decreased.

- Finding 4: Ed Blum and Chief Justice Roberts were wrong: There is no such thing as race-based admissions, and there never has been.

- Finding 5: The number of students who did not identify their race/ethnicity on their college applications grew significantly.

As I noted here, it is far too soon to attribute causes to enrollment outcomes this year. We barely know what happened with freshman enrollment post-SFFA; we certainly do not know why it happened. It is clear that the SFFA decision, which barred the consideration of race in college admissions decisions, had an impact on enrollment, but it is too soon to know precisely what that impact was, how widespread it was, how it interacted with other factors, and whether this year’s enrollment effects will persist over time.

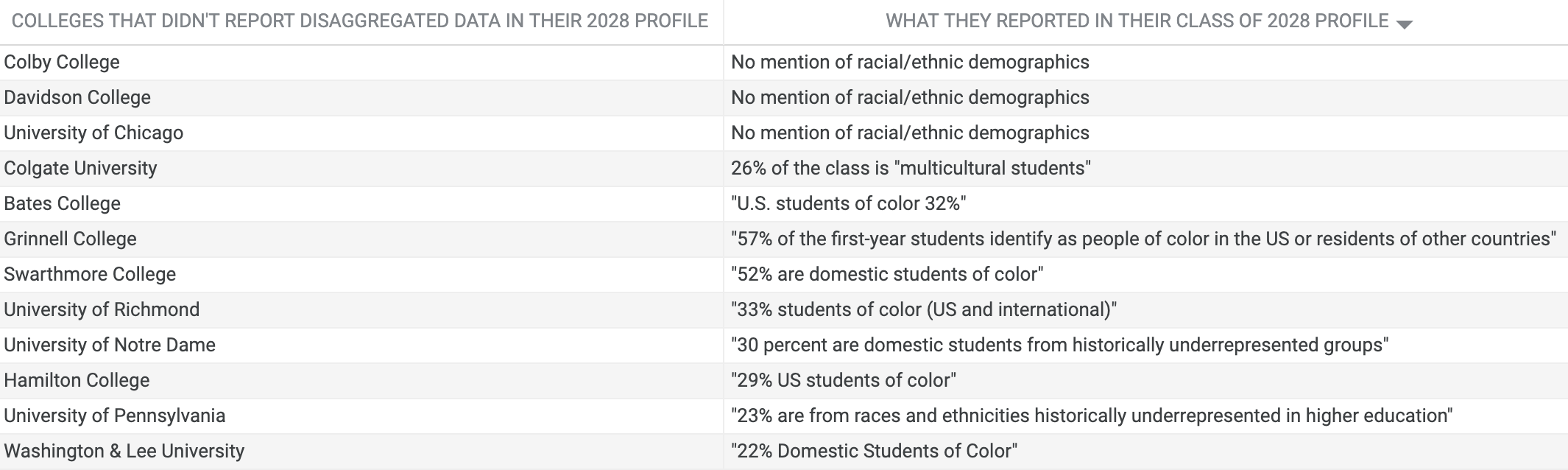

Finding 1: The variety in institutional data reporting needlessly complicates the analysis of the impact of the SFFA decision on college enrollment.

Comparing enrollment outcomes among institutions has been complicated by the variety of approaches they took to sharing data. Some institutions shared the demographic profile of the Class of 2028 using the racial/ethnic categories defined by the US Census and employed by the two major higher education data surveys: the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data Survey (IPEDS) and the Common Data Set (CDS). In these surveys, each student can be counted in only one category. Students who identify with two or more racial identities are counted in the category “Two or more races.”

In their own reporting on their admissions websites, some colleges and universities prefer to report students who identify with more than one race on their application to be counted in multiple groups. For instance, a student who identified as Asian and Black would be counted in both groups. There are good reasons to take this approach as a more accurate accounting of the racial and ethnic diversity of students on campus, but the problem with using this approach and not reporting data as it will eventually appear in IPEDS and CDS is that it not only renders making comparisons between institutions challenging but also makes comparing an institution to itself challenging. Researchers, reporters, and other interested parties rely on IPEDS and CDS to track institutional data over time and cannot rely on admissions pages that typically vanish after a year.

The most responsible institutions, such as Amherst and Stanford, reported the demographics of the Class of 2028 using both approaches. This is the best approach and, going forward, colleges and universities should use it on their admissions pages.

Several institutions that we tracked made it more difficult to see the impact of the SFFA decision on the diversity of their first-year class. Some institutions simply did not share their data. Others published their data in such a muddled way that it seems intended to confuse. Perhaps most frustrating are those institutions that published profiles that ignore race and ethnicity or that do not disaggregate by race or ethnicity, choosing instead to report meaningless categories such as “multicultural students.” (N.B., only communities can be diverse or multicultural, not people. The use of language like this suggests a lack of engagement with issues of diversity and culture and a centering of whiteness that should be a source of concern.)

Finding 2: The number of universities that saw shifts this year was unusual, but the sizes of demographic shifts at many institutions were not out of line with previous years’ shifts.

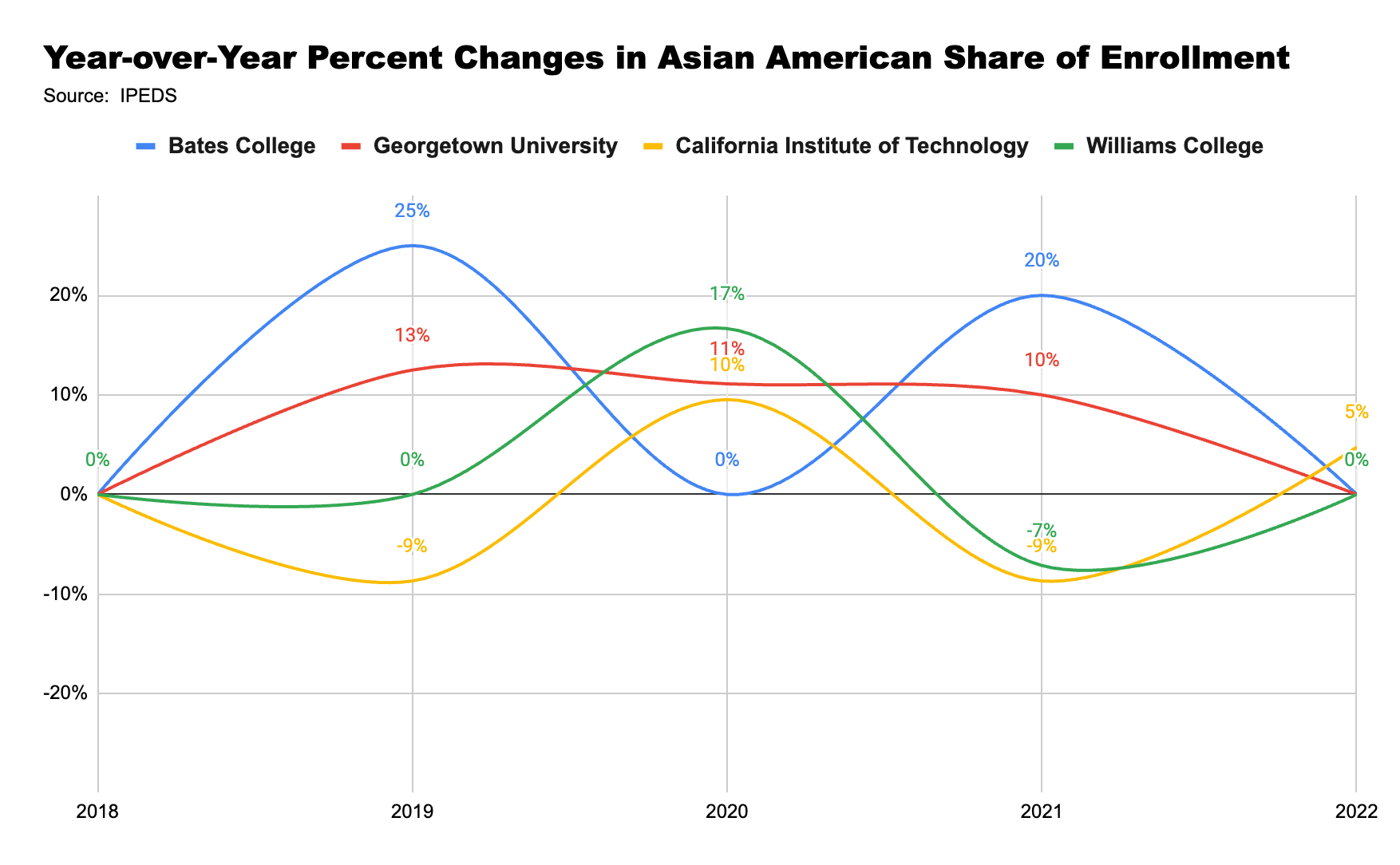

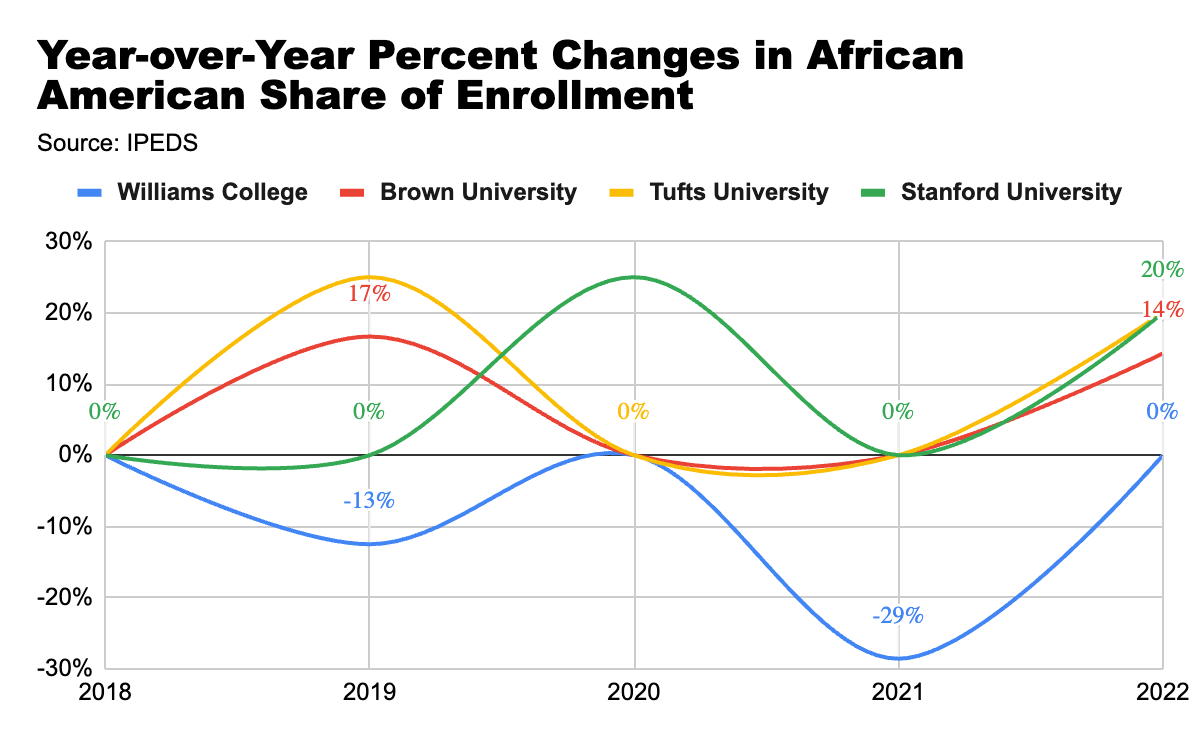

One of the unfortunate mistakes made in early discussions of post-SFFA enrollment was comparing the demographics of this year’s freshman class to last year’s. Comparing one year of data to another year is problematic because it treats the Class of 2027 as the norm and neglects the degree to which class demographics shift from year to year for a range of reasons. Significant single-year changes in enrollment demographics are not unusual, which is important to keep in mind when considering the impact of the SFFA decision.

Consider the following charts, which show the percent changes each year for five years in the shares of Black and Asian American enrollment at some of the institutions we tracked. At Georgetown, the percentage of Asian American students in the freshmen class grew by more than 10% three years in a row, while at CalTech and Williams the percentages fluctuated up and down.

At Williams, the pre-SFFA share of Black first-year students declined twice; in 2021, the decline was larger than the decline that Harvard or UNC-Chapel Hill saw this past year. Tufts saw fairly large increases in Black enrollment twice in five years.

Although it is perfectly normal to see large shifts in enrollment shares, it is not normal to see so many institutions experience large shifts in a single year. Clearly, the SFFA decision shaped enrollment at many colleges and universities, but it is simply not possible to say how much impact it had. It would be misleading to attribute all shifts in enrollment to the Supreme Court’s decision, but it would be worse not to track these shifts at all.

I landed on what I think is a very conservative (indeed, perhaps too conservative) approach to tracking demographic shifts. If the percent change was between -5% and +5% of the average shares in the classes of 2026 and 2027, I counted the change in enrollment share as flat.

Finding 3: The share of students who identify as Black/African American declined significantly at most highly selective institutions. The shares for other demographics mostly stayed flat or decreased.

Using the parameters described above, the only demographic for which there was a clear enrollment trend was for students who identified as Black/African American. At almost 80% of the highly selective institutions where we were able to track freshman enrollment outcomes, the share of Black students dropped by more than 5%. Worse, at twenty-four of these institutions, the share dropped by more than 20%, including six institutions where it dropped by more than 50%. The share grew by more than 5% at only two institutions in the tracker, Bowdoin and Northwestern.

Hispanic, Asian American, and White enrollment shares did not follow a clear pattern. At a majority of the institutions we tracked, the Hispanic enrollment share stayed flat or increased. The White enrollment share stayed flat or declined at two-thirds of the colleges and universities we tracked, while the share of first-year Asian American students declined or stayed flat at nearly three out of five institutions.

Finding 4: Ed Blum and Chief Justice Roberts were wrong: There is no such thing as race-based admissions, and there never has been.

What happened with the Class of 2028 certainly did not follow the pattern that people would have expected if they believed the argument of the organization Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) and its founder, Ed Blum. SFFA tried and failed to convince three courts that Harvard and UNC-Chapel Hill discriminated against Asian American students and provided an unfair advantage to Black and Hispanic students through the use of what they called “race-based” admissions. It was only when these cases reached a Supreme Court heavily shaped by Republican presidents and by Donald Trump in particular that SFFA found a sympathetic response. Although the majority opinion pointedly never uses the phrase “affirmative action,” its author, Chief Justice John Roberts, repeatedly uses the term “race-based admissions” rather than “race-conscious admissions.” In doing so, he reveals his and the Court’s ignorance of how a holistic college admissions process actually works.

Put simply, there is no such thing as “race-based admissions”—not in the sense that anyone gets into a college based on their race. The basic fact that the Court failed to grasp was that no one gets into any highly selective college based on any single factor, whether that factor is their race, legacy status, athletic ability, or whatever. At institutions such as Harvard and Chapel Hill, there are always far more highly qualified applicants than there are seats available in the freshman class. Single factors can make a big difference among highly qualified applicants, but that is a long way from saying that an applicant got in because of that factor alone.

If college admissions pre-SFFA was “race-based” in the way that Blum, Roberts, and others fantasize it to have been, then we would expect to see enrollment shares at institutions that formerly considered race in admissions go up across the board for Asian American and White students and decrease for Black and Hispanic students. This is not what happened. The reason why Blum’s racial fantasies about college admissions did not come true is quite simple: college admissions is complex.

Finding 5: The number of students who did not identify their race/ethnicity on their college applications grew significantly.

Post-SFFA, just about every university and college in the country continued to ask students to self-identify their race/ethnicity. The only exception I know of is MIT, which is the rare private college that does not use the Common Application. In a move that can only be described as bizarre, MIT removed the race/ethnicity question from its application, even though it is easy to redact responses to the question about race, which is what the vast majority of institutions affected by the SFFA decision did this past year. MIT’s wrong-headed response to the SFFA decision is not only unnecessary; it is also harmful because it prevents the admissions office from determining who was in its applicant pool and how well it recruited students to apply and enroll. Given the impact that the elimination of the question about race/ethnicity may have had on its shocking enrollment numbers this year, it would be surprising if MIT carried on with this odd choice—a choice made by no other institution as far as I can tell.

Although almost all colleges ask students about their race and ethnicity on their applications, there has long been chatter in some applicant circles and among some independent college consultants about whether it is wise to self-identify by race, particularly if an applicant is Asian American. A brief filed by Students for Fair Admissions in the lead-up to the Supreme Court case cited the Princeton Review’s 2004 guide, Cracking College Admissions, which advised students, “If you are an Asian American—or even if you simply have an Asian or Asian-sounding surname—you need to be careful about what you do and don’t say in your application.” We cannot know who opted out of self-identifying their race/ethnicity on their applications this year, but when the economist Zachary Bleemer studied non-reporters on applications to schools in the University of California system after Proposition 209 outlawed the consideration of race in admissions, the majority were white. He found that the race/ethnicity of 88% of the non-reporters in the Classes of 2000 and 2001 could subsequently be identified and that two-thirds were white, 29% were Asian American, 3% were Hispanic, and 1% were Black.

Whether checking a box or boxes identifying their racial/ethnic identity could hurt applicants or not, the question became moot after the Supreme Court’s SFFA decision Since admissions officers are no longer seeing which of these boxes are checked, there is no point in not checking them. You would expect the number of students not identifying their race on their application to go down, but that is not what happened—at least not at the highly selective colleges that we tracked. On average, the share of students who did not identify by race or ethnicity essentially doubled, going from 3% to 5.8%. Some institutions, such as Stanford, Smith, WashU, and USC, saw much larger increases. It is hard to identify commonalities or patterns, other than that most colleges that reported on this category also reported large changes.

A note of caution is needed here. The comparisons in the chart are between the averages of the classes of 2026 and 2027 and the percentages reported in the class of 2028 profiles. These 2028 percentages may decrease when Common Data Set numbers for the class of 2028 are released in 2025, as students have opportunities to self-identify their race and ethnicity upon enrollment. For example, Harvard reported that 4% of the Class of 2027 did not check a race box, but when you look at Harvard College’s Common Data Set survey for that class, the share of students in the “race and/or ethnicity unknown” category is just 2%. This suggests that half the enrolled students who did not identify their race when they applied to Harvard did so later. It is very possible that something similar will happen with this year’s cohort. As a result, it is likely that at some institutions the demographics of the class of 2028, including students whose race/ethnicity is unknown, will shift in the data reported to the Common Data Set surveys released next year.

What happened at the UC system is another reason to be cautious interpreting the current data. It could well be the case that the majority of the students who did not indicate their race or ethnicity on their application were White and Asian American, and we will see an increase in those demographic shares when colleges start publishing their Common Data Set surveys in 2025. It might also be true that the demographics of non-reporters will not look the same this year as it did two decades ago in California.

In order to estimate the potential impact that the increase in students not reporting their race/ethnicity on their applications may have had on class diversity, I created a hypothetical comparison that made the extreme (and likely) erroneous assumption that all the growth in students whose race is unknown came from students who are White or Asian American. I calculated the percent change in the combined share of White and Asian first year students in the Class of 2028 versus the average of the Classes of 2026 and 2027, which is represented by the blue dot in the chart. Then I added the difference between the share of the class that did not report their race and ethnicity in the class of 2028 and the average of the classes of 2026 and 2027 to the combined share of White and Asian American students and recalculated the percent change from the previous two years (the red dot). We only calculated this change for institutions that reported the demographics of the class using IPEDS/CDS methodology. Before the adjustment, the combined enrollment share of Asian American and White students was lower or flat at slightly over half of the seventeen institutions; after the adjustment it was lower or flat at slightly under 40% of them.

Conclusions?

It is too soon to reach conclusions about the long-term impact of the SFFA decision. Honestly, we should be careful with the short-term impact.

What we have seen is a single year of preliminary data from a relatively small sample of four-year institutions reporting outcomes in different ways. We will likely see some revision of enrollment numbers at many institutions when their Common Data Set surveys are released in spring and summer 2025 and when IPEDS data are published in fall 2025. We will also likely see enrollment demographics change again for the Class of 2029 as institutions continue to adapt to the post-SFFA admissions environment and react to this year’s outcomes.

The good news is that in a couple years we will have a better understanding of college admissions processes thanks to changes being made to IPEDS. In December 2025, for the first time, IPEDS will ask colleges and universities to share demographic data for applicants and admitted students. This data will provide researchers, policymakers, students, and the institutions themselves with deeper insight into the causes of demographic shifts in enrollment and will help shape best practices. After all, enrollment numbers show us only the end of a long process. They reveal little about the rest of the admissions process, including, but not limited to, the following:

- Applicant recruitment strategies and practices, for example:

- High school visits

- Fly-in programs targeting underrepresented student populations

- Outreach shaped by census tract data

- Heavy reliance on feeder high schools, especially independent private schools and wealthy public schools

- Heavy reliance on athletic recruiting

- The targeting of transfer students

- The creation of MOUs with high schools or school districts that have large populations of underrepresented students

- The employment of a diverse staff in admissions offices, including tour guides, who are ready to discuss campus diversity

- Admissions policies and practices, for example:

- The use of census tract data to understand an applicant’s home and school context

- Legacy preferences

- Early decision and early action

- Athletic recruiting

- Heavy preferences for students from independent schools, wealthy public schools, and other feeder high schools

- The prioritization of Pell-eligible students

- The prioritization of first-generation students

- Yield strategies

- Competing institutions

- Financial aid

Better data on the entire admissions process will allow us to ask better questions about how these and other factors come into play in shaping the ultimate composition of first-year classes.

In the meantime, we will continue to track enrollment data. We expect to release an update on enrollment outcomes, using CDS data for a much larger pool of institutions, in the summer of 2025.

This post was edited to include new data on November 14, 2024.