When public flagship universities have to grapple with decreased state financial support, low-income and racial minority students pay the price in a variety of ways. As public universities look for ways to increase revenue in a response to state funding cuts, increasingly they have turned to policies that favor students who can bring in tuition revenue. Not coincidentally, we’ve seen a retreat at those same public universities in making a meaningful commitment to student body diversity and socioeconomic opportunity. (Psst, University of Virginia, we’re talking about you among others.)

First things first. It’s well understood that when states are pinched to balance their budgets, they typically cut funding for public colleges and universities. Institutions, to make ends meet, pass on those budget cuts to students in the form of higher tuition. In turn, students and families borrow ever increasing amounts.

The median public research university saw an average 26 percent cut in state support between 2008 and 2013. A study recently reported in Inside Higher Education found that over the past three decades, for every $1,000 per-student cut in state and local funding, students experienced a $257 increase in tuition and fees. Recently, that ratio has risen even higher. Since 2000, the increase in tuition for every $1,000 cut has risen to $318, compared to $103 before 2000. But the state disinvestment in higher education story runs deeper than just driving higher tuition.

Growing Numbers of Out-of-State Students at State Universities

Public colleges have stepped up their enrollment of out-of-state students who pay higher tuition levels than those from in-state families. For example, in-state students made up only 37 percent of the University of Alabama’s Class of 2018, compared to 73 percent a decade earlier. The University of Alabama is not unique.

The Washington Post analyzed in-state vs. out-of-state student enrollment at 100 universities, including each state’s flagship university and one additional public university. Seven institutions saw their in-state share of the population drop at least 20 points between 2004 and 2014. Overall, 74 of the 100 public universities analyzed saw their share of in-state students drop. Not coincidentally, 67 of these universities also saw decreases in state appropriations over the same period.

Public Flagships Have Increased their Non-Need Based Aid

Public flagships also increasingly are shifting student aid policies away from providing need-based assistance to instead emphasizing non-need based or so-called merit aid. Again, it’s an effort to recruit students who will ultimately bring in more tuition revenue.

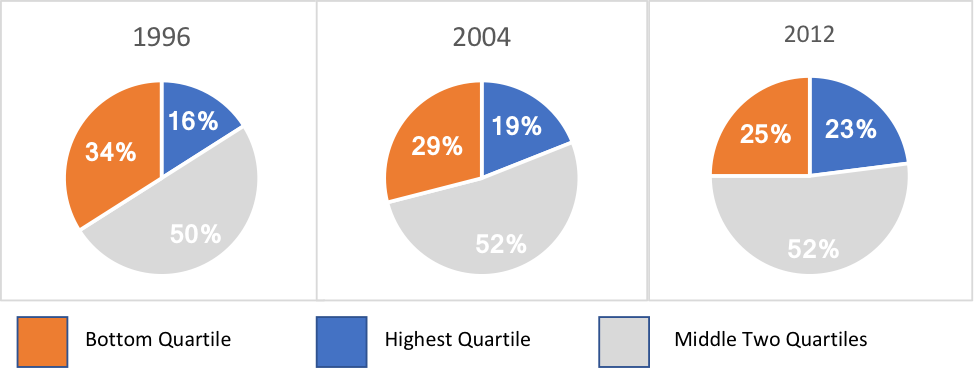

In 1995, public flagships dedicated about twice as much financial aid to those students from the bottom income quartile as those from the top. Some 34 percent of institutional financial aid went to students from families in the lowest income quartile and 16 percent to students in the highest income quartile. By 2004, the distribution had shifted to 29 percent going to the neediest students and 19 percent going to students from the highest income quartile. In 2012, the latest data available, the gap between aid distributed to the students in the highest and lowest income quartiles became even smaller—25 percent of institutional aid went to students from families in the bottom income quartile while 23 percent went to students from the highest income quartile.

Source: The Out of State Students Arms Race

Today when you consider public and non-profit private colleges, institution-decided financial aid is used more often than not as “bait” intended to hook students from wealthy families as opposed to help students from hard-pressed working class and low-income households.

Increased tuition and decreased aid push out low-income and URM students

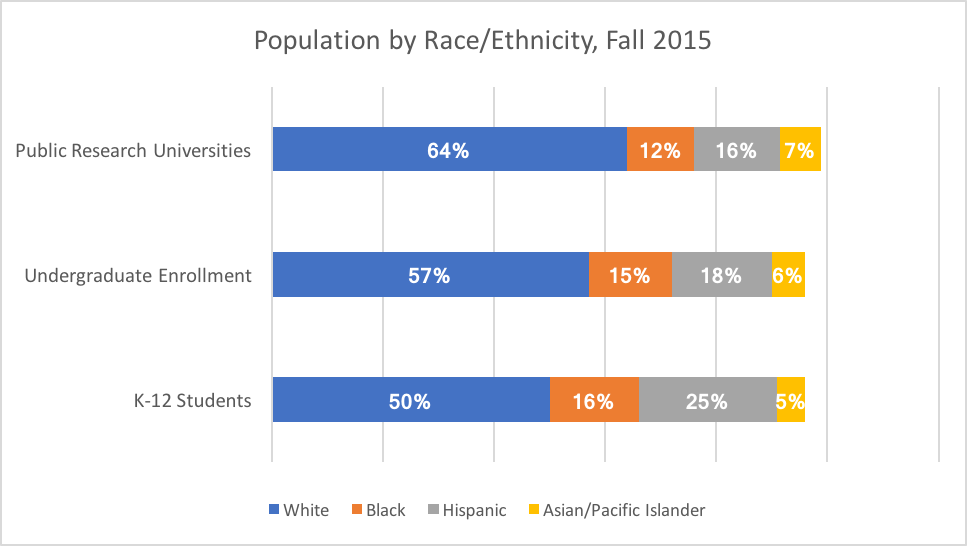

The combined effect of institutions increased enrollment of out-of-state students and shift to non-need based aid as responses to decreases in state funding has pushed low-income and underrepresented students out of public flagships. The students that public flagships have recruited from out of state are more affluent and less likely to be Black or Latino. As the proportion of non-resident students at state universities has grown, the proportion of underrepresented minority students has declined, as has the proportion of students from low-income families. Enrollment by race at public research universities does not reflect overall undergraduate enrollment by race.

Source: The Digest of Education Statistics

Calcifying Inequity

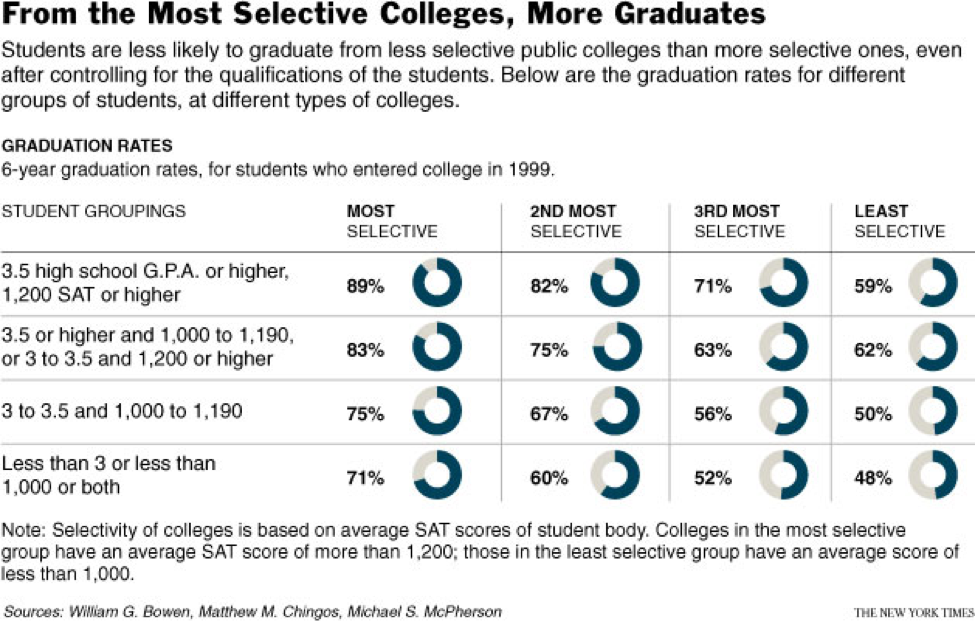

The effects of state disinvestment stretch beyond under representation in admissions and enrollment. Graduation rates are typically higher at selective institutions: selective institutions have a graduation rate of 82 percent compared to the 49 percent graduation rate at open-access universities. So, to the extent flagships become less racially and socioeconomically diverse, to the extent we increasingly segregate our higher education system, we dramatically undermine racial and socioeconomic mobility for society as a whole.

Similarly prepared students do better at selective institutions than their peers at less selective institutions. The pattern holds when looking at subgroups. For example, Latino students are 21 percentage points more likely to graduate from a selective institution than from a less-selective four-year institution (68 percent versus 47 percent).

In the face of rising costs, telling higher-achieving students of lesser means to simply choose cheaper schools does them a disservice regarding their chances of graduation and post-college success. In other words, state cuts to higher education are not only boosting tuition and increasing student debt, they’re undermining geographic communities and calcifying inequity.

The very recent upward trend in state appropriations to higher education must continue so public flagships have the resources they need. But public flagships are not off the hook when it comes to making a meaningful commitment to diversity and opportunity.