To me, one finding from our recent deep dive into Massachusetts public higher education has been particularly shocking. Bay State students of color are much more likely to attend a community college than the national average and much less likely to complete their degrees.

Massachusetts Black high school graduates are 50 percent more likely, and Latino graduates are nearly twice as likely as their white peers to attend an in-state community college. Yet, Black students are 54 percent less likely than their white peers to complete and Latino students are 48 percent less likely to complete an associate’s degree program within 3 years. And that’s for first-time, full-time students. Completion rates are typically much, much worse for part-time students and non-first-time students.

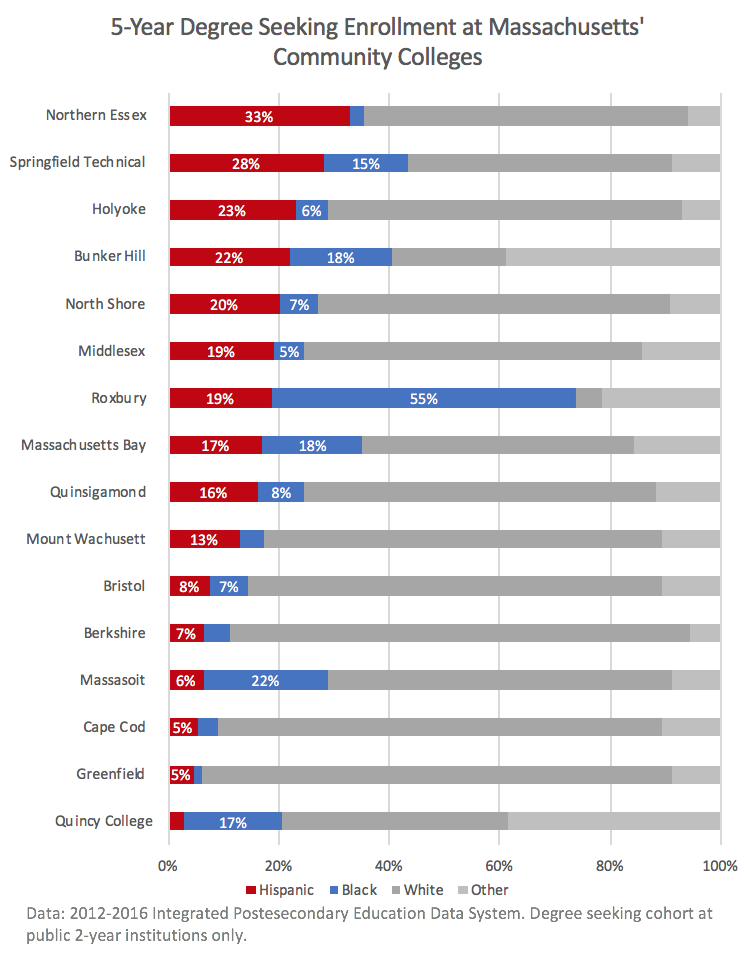

The following chart captures the racial and ethnic composition of the degree-seeking cohort by combining data from the past five years (to increase sample sizes). As is evident, different schools serve different populations, but perhaps the most important thing to recognize is how disproportionately represented students of color are, overall.

A look at the five-year average of Massachusetts’ 18-24 year-old (“college age”) population finds only 9 percent of the state’s population is Black and only 14.3 percent of the state’s population is Hispanic or Latino. Yet, when one examines Bunker Hill Community College enrollment, for example, there are over twice as many Black students, and over one-and-a-half times as many Latino students as would be representative of the state’s college-age population,

Moreover, in general, the completion rates at these community colleges are poor. Only one of these community colleges has an overall first-time, full-time degree seeking student 3-year completion rate over 25 percent — Greenfield, at 26 percent. Unfortunately, Greenfield also had the lowest enrollment rates of Black (1 percent) and Latino students (5 percent). It might as well be in Vermont.

When one looks specifically at Massachusetts’ community college Black student 3-year completion rates, no institution has a success rate above 15 percent, and for Latino completion rates, the only institution to average above 20 percent was Berkshire Community College, at 22 percent.

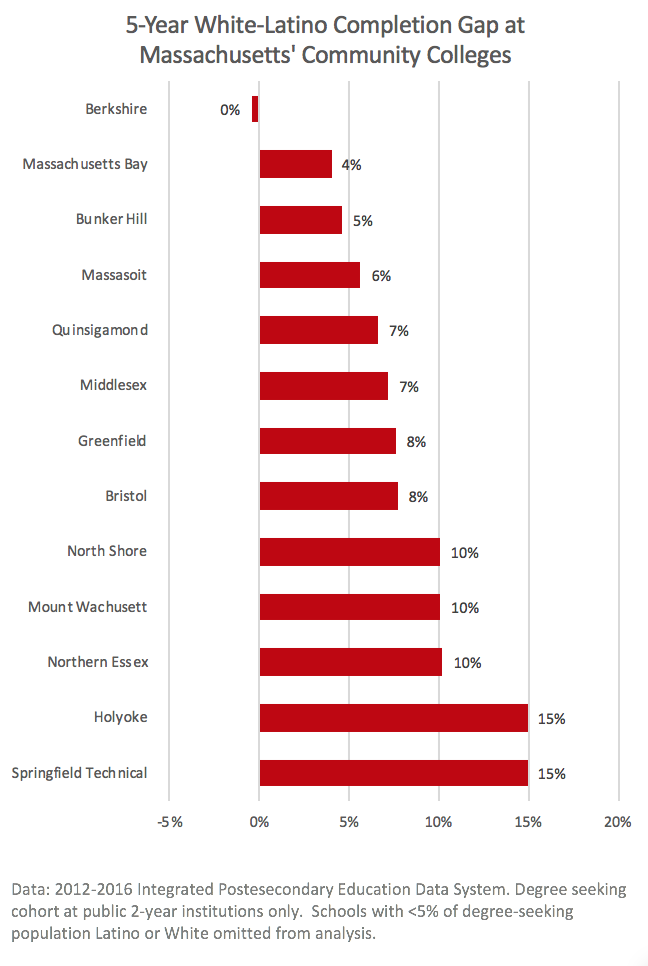

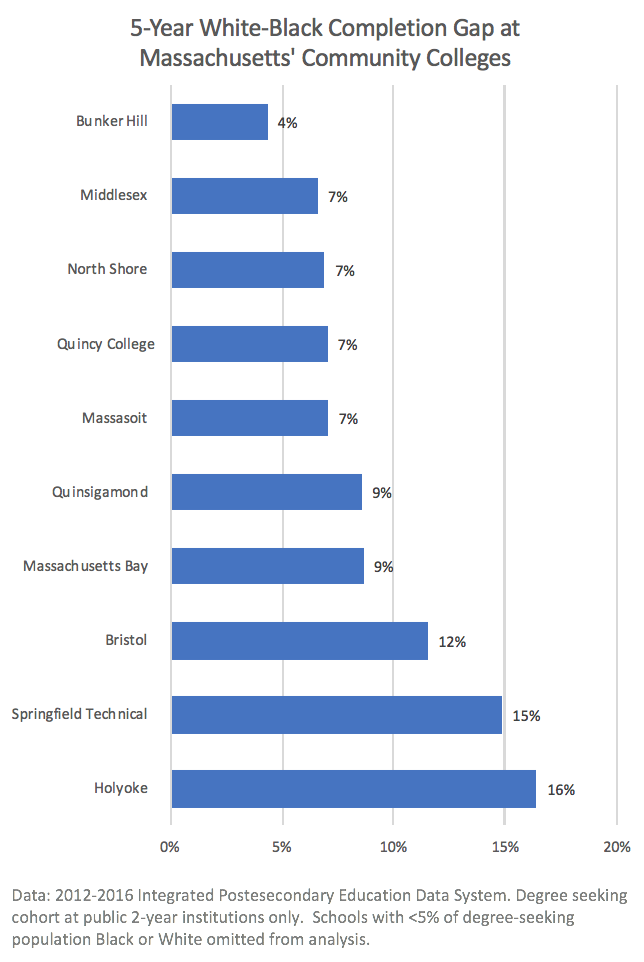

Worse still are the completion gaps facing students of color across these institutions. The charts (below) illustrate the 5-year graduation gaps between students of color and their white peers. From our analysis, it is clear that some institutions work and are more successful in closing their gaps better than others. One concerning actor is Springfield Technical Community College – which has one of the highest overall completion rates (still only 20 percent), one of the highest proportions of enrolled students of color, and yet also has some of the largest gaps between white students and their Black and Latino peers – both gaps are 15 percentage points wide. Put another way, despite high overall completion rates, a Black or Latino student at is less than half as likely as a white student to graduate from Springfield Technical.

So, what can communities and colleges do to close gaps and raise overall completion rates? Well, the single greatest predictor of college success is academic preparation. To get better results, we recommend making the MassCore college preparatory track the default track for every student, and crucially, also provide high schools and non-profit community-based organizations additional resources to provide academic support for those students who are behind. That means everything from one-on-one tutors to extended learning time during the year and over the summer. Massachusetts has a history of raising standards and providing additional aid for extra support to boost achievement. It needs to double down on that strategy in high schools.

We also recommend providing targeted state resources to community colleges and non-profits in order to provide proven supports like counseling, child-care, and transportation aid for struggling students. In return, we suggest that institutions need to be held more responsible to governments and accrediting agencies for their gaps in access and outcomes. If we give institutions additional resources to provide better services and close equity gaps, then we expect those resources to be put to good use or risk consequences ranging from altered institution leadership to repayment (potentially with interest).

# # #

For a more detailed discussion of these policy proposals, and our comprehensive college promise plan for Massachusetts, please see our recently released report: No Commencement in the Commonwealth: How Massachusetts’ Higher Education System Undermines Economic Mobility for Latinos and Others – And What We Can Do About It.